Creatives voice concerns over AI music

April 11, 2023

Creative work that was once possible only after years of training and practice can now be done in mere minutes, thanks to advances in artificial intelligence. Lately, creative fields have felt the brunt of this ever-developing technology, but a field that’s not being talked about as much is music.

Programs like Amper Music, Jukebox, Soundraw, Soundful, Aiva and Google’s Magenta are only a few AI music generators that enable everyday people to produce an entire library of music in under a day.

The technology has left many musicians and producers divided over the industry’s uncertain future.

“It’s like when cameras came out, everybody thought there was gonna be no more painters, but we still have painters. They just do a different thing. It’s not like we’re all going to disappear now,” said Radiance Francois, an Eastfield student and singer/songwriter.

A common argument observed in social media is how this technology may make music more accessible to individuals who are disabled or otherwise economically disadvantaged, thus lacking resources to pursue their passion.

“It’s advantageous to put someone with limited means in a position to express themselves in a way they feel reflects their truest intent to a greater degree than they could have been able to do 20 or 30 years ago,” said Eddie Healy, an Eastfield music theory instructor.

Francois proposed that AI technology may also make music more enjoyable for those who aren’t well versed in certain aspects of music creation.

“I mix and master my stuff, but to have an AI do it makes it so much easier, faster, so I can focus on the things I want to,” said Francois. “ If the AI can do it quicker, I can focus more on the writing and creative side I enjoy rather than the mixing.”

While some may benefit from using the technology, Healy argues that they would lack true ownership of their work by not understanding how to produce the sounds within. He said that society has become increasingly disconnected from an understanding of music and that AI may worsen this.

“People can get inspired all the time. That’s different than just [stealing] clips. There has to be a certain threshold before it’s considered your voice,” said Francois referring to music AI generators training on pre-existing materials to create their sounds.

Musicians like Healy have said that AI may make it easier for artists to express themselves, noting artists who started off sampling but became increasingly independent over time, like Dr. Dre.

The lack of training required might also affect how music is taught in schools.

“AI is just a tool. It’s like giving someone a state-of-the-art piano, but they don’t know anything about playing the piano,” said Eastfield music instructor Oscar Passley. “I think if you have savvy enough people behind it, then they will innovate.”

Healy also said that AI is useful as a learning tool like YouTube tutorials and much more.

Like AI-generated art, some creatives have weighed the possibility that AI music will lead to the death of the instructor.

“Just about everything that isn’t a teacher has the potential to minimize the role of a teacher,” Healy said. “There’s always a point at which you hit a wall and need further discussion on a topic that a YouTube video is just not going to help you on.”

Healy doesn’t plan to implement any sort of AI tech in his own classroom but is open to teaching his students how to use it more responsibly. His greatest hope is that students understand how to achieve the effects AI enabled them to so they can have a greater degree of ownership over their craft.

“Being able to combine traditional music learning with everything new that’s happening is a must to stay relative and relevant in the industry,” Passley said.

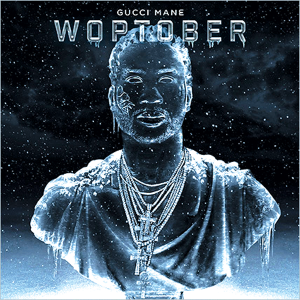

While many may benefit from increased accessibility to music creation, there’s also a darker side to AI’s ever-growing role in the music industry: In 2020, Jay-Z’s team copyright claimed a YouTube video deepfake of him rapping Hamlet and Billy Joel. After a while the video was reinstated, but it did highlight a concern many creatives have over their vocals being used without consent, even for satirical purposes.

Jay-Z’s case was only the tip of the iceberg as deepfake AI tech has only become more efficient. Social media is currently teeming with countless videos spoofing famous celebrities, fictional characters and, most popularly, former U.S. presidents saying anything the creator desires.

“The technology is always way in front of legislation and policy,” Passley said. “I think it’s just uncharted territory and we’ll see the government catch up later on.”

Washington state legislators recently proposed a bill for protections against AI deepfakes. As the technology becomes more efficient many are worried how this will affect perceptions of truth and reality.

“I think we already struggle to discern reality,” Healy said. “It’s why we have large swathes of our culture that have become conspiratorial. And I think it’s easy to feed the conspiratorial mind by creating so much that is farce.”

In the past we’ve seen technology improve to the point that studios are able to resurrect deceased actors. Famously, the Star Wars franchise utilized CGI to generate characters like Princess Leia and Grand Moff Tarkin with uncanny realism.

Like Jay-Z’s case, this also has leaked into the music scene with projects like “lost tapes of the 27 club” utilizing AI technology to create songs from artists who have died like Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Amy Winehouse and many more. While created to highlight the mental health struggles facing many young musicians, there’s been a question across social media about how using the voices of artists who aren’t alive to give consent is deeply problematic.

Healy said if their estate consents it should be fine but worries how we’ll communicate what’s real and isn’t.

“I hope that we have become sufficiently adept at communicating with one another that future generations are going to look back at this time and say that wasn’t actually Jim Morrison, or the actual guy from ‘Star Wars’,” said Healy, “I think the most destructive aspects of our culture are the ones that are born out of ignorance.”