By JAMES HARTLEY

@JamesHartleyETC

The Dallas County Community College District is planning changes to help counter low success rates and high poverty and illiteracy in Dallas County.

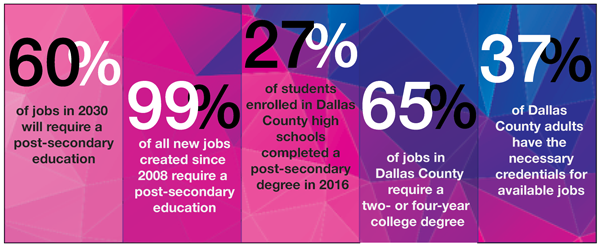

DCCCD Chancellor Joe May said more than 1 million Dallas adults will be illiterate by 2030 and 60 percent of all Dallas-area jobs will require post-secondary degrees.

The district plans to increase communication among campuses, expand corporate partnerships, retrain academic advisers and change the way colleges attract new students.

This plan, called the network, is intended to improve the local economy and education rates by making sure all high school graduates are college ready with at least 15 credit hours, dedicated to a career path by grade 9 and committed to attend and complete college.

To achieve this, the DCCCD is offering last-dollar help to give Dallas County high school graduates coming to a district college the opportunity to get a tuition-free education.

The district is also forming partnerships with other schools, like Southern Methodist University and the University of Texas at Dallas, to give students access to a free or cost-reduced bachelor’s degree and building corporate partnerships to help non-transfer students get a job right out of college.

Corporate partnerships reach beyond just job opportunities for DCCCD graduates. In some Dallas area schools, 11 American Airlines employees work with students as a part of one partnership.

The plan is also designed to save Title III and Title V funding, which allow district colleges to offer federal financial aid. Because of low success numbers, this funding is at risk.

[READ MORE: Dallas Promise provides free tuition for students of partnering high schools]

Students have access to assistance with food security, mental health resources and financial aid currently. With the network, May hopes to see that assistance expand to address homelessness and other areas of insecurity that may impact a student’s ability to succeed.

Dallas County is last among cities in the U.S. in terms of high school graduates completing a two- or four-year degree, according to the National Student Clearinghouse.

May said this is because of a design flaw.

Until recent years, a high school diploma was enough to get a middle class job, he said.

But that’s changed.

“We only needed about a quarter of the population with some kind of degree,” May said. “We designed higher education to weed out people, not to educate at the level we need to be educating at. The game’s changed,. The rules are different.”

“My sense from those who attended the presentation, saw the slides and heard the chancellor’s remarks, that they are compelled that, yes, in the district we can do better in meeting the needs of our community, getting our students to complete,” Faculty Association President Matt Hinckley said.

“Many of the students who intend to transfer and even those who complete our core curriculum or one of our Associate of Arts or Associate of Science degrees end up not transferring, for whatever reason.”

Hinckley, a history professor, said he has found two responses from faculty. Those who were present at the event seemed less concerned or even supportive of the plan while faculty who only saw the slides expressed more concern about the direction the district is moving.

“It’s striking to me how different the interpretations are,” Hinckley said.

Some faculty told Hinckley they that academic programs are being overlooked in favor of skills training such as welding, auto work and heating and air conditioning repair.

[READ MORE: The case for more space]

This feeling stems from a historic trend of elevating vocational training over academics paired with the national political climate with disdain for higher education, especially liberal arts, Hinckley said.

While he believes concern about a shift of focus from academics to workforce and vocation training may be a valid concern on the national level, it doesn’t appear to be the case in the DCCCD.

During the early 2000s, the DCCCD began cutting back on vocational and workforce programs. Hinckley said faculty have been concerned since this trend reversed when May became chancellor.

“A few of them who remarked to me said they feared that we might be becoming an entirely technical or vocational college,” Hinckley said. “I think, even though I’m an academic credit and transfer faculty, I think he [May] very correctly added emphasis to workforce and career technical education programs where it had been lacking for the last 15 years.”

He said the increased attention for these programs could create a feeling among for-credit faculty that they are being overlooked or undervalued.

Hinckley said that no faculty in academic, credit rewarding divisions have been laid off since the DCCCD began the push for more increase resources for workforce and vocational training and he expects more will actually be hired next year.

May believes the DCCCD can change that design, with the right moves going forward.

One of the changes that may have the biggest impact is by connecting with students before they graduate high school.

“I think we most agree that the old model of waiting for a student to graduate high school before connecting doesn’t work,” May said. “It’s just simply too late in the process to change what’s going on.”

Programs like the early college high schools and the Dallas County Promise will be the spearhead in the effort to get more high school graduates to complete a degree.

The problems with completion may run deeper, though, May said.

About 18 percent of first semester students do not complete a single course in the DCCCD, according to institutional research. More than 80 percent of high school graduates are not college ready when they receive their diplomas, 41 percent do not enroll in their first year after graduation and 52 percent do not continue into their second year of college.

[READ MORE: UNT-Dallas, Eastfield begin dual enrollment]

“I truly believe we have students who are suffering in ways like never before,” May said. “We also are seeing too many students who are falling through the cracks. Eighteen percent of our first semester students never finish a course. We cannot afford for one of them to not complete, not be successful, much less 18 percent.”

May said the district would look to students who have found success on their own, without using only the tools provided by the district. Many of these students, he said, attend multiple colleges and create networks with other successful students outside of the communication provided by the DCCCD.

Eastfield President Jean Conway said she is excited about the changes.

“The district is planning to move forward in a way that hopefully we make a true difference, not only in students lives but we believe we make a difference in the city, the culture, the economy, the county,” Conway said. “By doing the things that the chancellor has proposed in a network model, we have an opportunity to be a part of that.”

Hinckley said that the number of students who do not transfer or complete degrees is a sign that change is necessary. He said the Dallas County Promise will likely help.

He also believes Guided Pathways, which will tell students which classes to take and when, aid for students facing hunger or housing insecurity and assistance for students with mental health needs, all of which are receiving increased attention under the network, will all help students complete and transfer to a four-year institution.

He believes a move more toward a single institution mindset rather than being seven separate colleges under an umbrella, which the network plan is a move toward, will be a great help to students and success rates.

“There are differences between the seven colleges, but the perceived differences are greater,” Hinckley said. “I’ve worked at two different colleges in the district. I’ve been to all seven. At all seven colleges, people care about students. That’s why we do what we do, because we care about students. That’s a unifying culture.”

https://eastfieldnews.com/2018/03/07/i-think-of-it-as-a-nightmare-for-daca-students-uncertainty-continues/