By YESENIA ALVARADO

@YeseniaA_ETC

In the middle of the day, Morty Ortega rides in the front seat of his fixer’s truck. Writer JK Nickell sits behind him as the truck slows down. Ortega waits anxiously as the fixer puts the truck in park, opens the door and heads off with a box of cigarettes in his hand.

Hearts pounding, the two journalists wait silently in the vehicle. If something goes wrong they could be arrested or killed for what they’re doing. Ortega watches out the window as he waits for the fixer to return.

When the fixer walks back into Ortega’s view, he’s no longer carrying the cigarettes. Silently, he gets back into the truck, puts it into gear and drives. Nickell does his best to stay out of view as they pass cigarette-bribed, armed men —probably government officials — into “Kachinland.” The fixer said Ortega looked “Kachin enough” to be seen in daylight.

In 2011, more than 100,000 Kachin people were displaced after a cease-fire between the Myanmar Armed Forces and the Kachin Independence Army was broken. Conflict across the Kachin state drove many refugees into China.

Ortega wanted to show how conflict affected the Kachin people, forcing some into makeshift refugee camps and others into the army.

This routine of offering bribes for passage happens about half a dozen more times as they visit different pockets of Kachin “villages.”

Each time they cross Chinese border checkpoints they face more danger. But the driver, who knows exactly what time the guards were either taking a tea break or a nap, easily drives past these checkpoints.

After spending a week in Kachin’s capital, Laiza, Ortega and Nickell spent a week in Mai Ja Yang meeting Kachin refugees and spending time with the KIA. The pair became the only two Western journalists who witnessed the Chinese government kicking out Kachin refugees out back into Myanmar.

As they headed to the Chinese airport, word of their trespass got to the guards at the border. The number of guards doubled.

They were now faced with the possibility of getting detained because, although they had tourist visas, they were doing prohibited journalism work.

“We had to come up with this fake story of how we got lost and we were on a tour,” Ortega said. “We didn’t speak the language, the tour guide didn’t speak English, and we had just gotten off the path. So I had a few nice tourist pictures on my camera, but the rest of my memory cards I hid under the insole of my shoe.”

Despite the danger faced and the exclusive story Ortega was able to tell, his work was never picked up by a news agency.

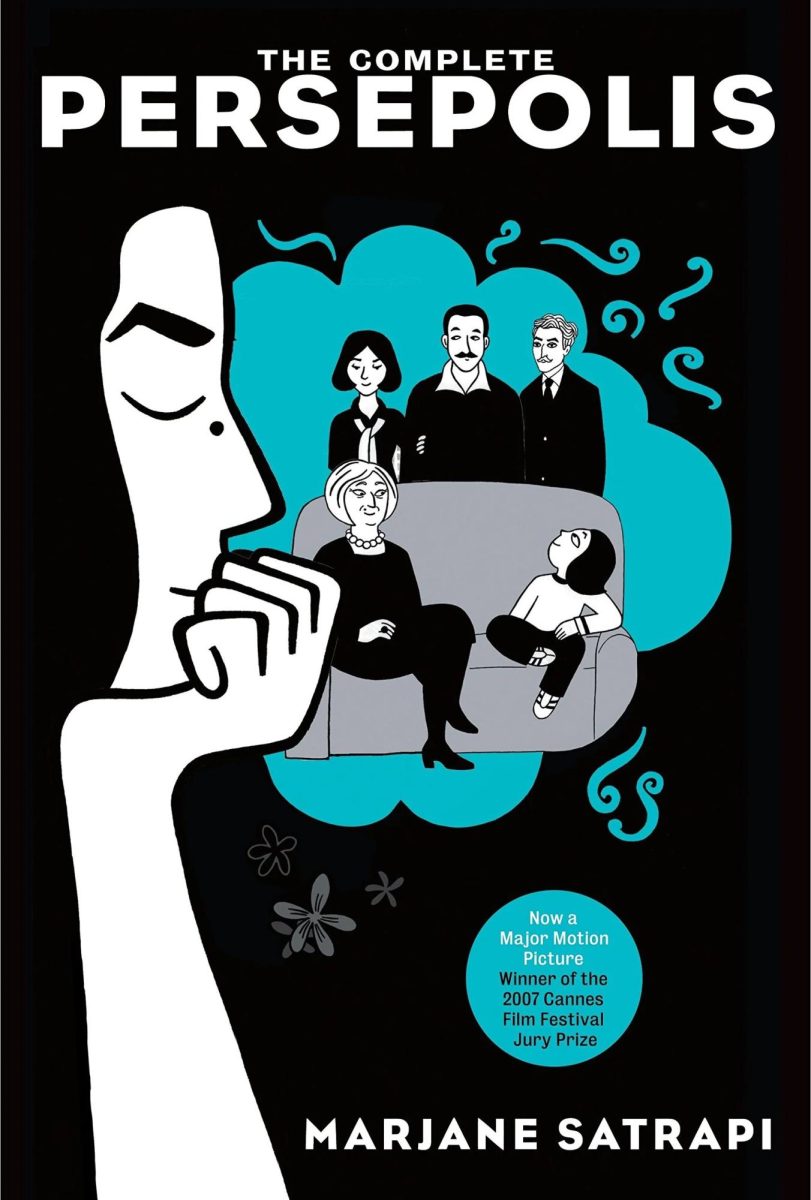

Ortega, a freelance narrative and visual journalist, visited campus Feb. 13 to share stories about his career, including the rescue of 33 Chilean miners trapped in a collapse. The event was sponsored by the Common Book Committee in connection with “Deep, Down, Dark,” the 2017-2018 common book.

Ortega has photographed for Getty, Hartford Courant, German Press Agency dpa, La Tercera and Las Ultimas Noticias in Chile, Delta Air Lines’ SKY and Korean Air’s Morning Calm magazines. He’s also worked for education institutions, journalism conferences and the Chilean government.

Ortega wasn’t always drawn to photojournalism. As a high school student, he enjoyed photography only as a hobby. It wasn’t until his senior year when he considered photography as a potential career.

He was given the option to take a college class at the University of Connecticut while still in high school. He decided to take a fine art photography class and found he had a passion for it.

As an undergraduate student, he took a documentary photography class, a genre between fine art and photojournalism. That was his bridge into telling stories with photographs.

“I struggled to make photo art that was interesting to me,” Ortega said. “It was that desire to tell something else in photos apart from the fine art perspective. Like, a lot of fine art is about the artist making a statement or something very personal. From a fine art perspective, ‘look at what beauty I can capture. Look at my beautiful pictures.’ Where in photojournalism it’s more about ‘look at what these people are going through. Look at this issue. Look how climate change is affecting this community.’ “

[READ MORE: Looking at the black experience through its musical influence]

During a fine art course, one of his professors showed the class photojournalism, and Ortega realized that he admired the work.

He didn’t know that years later he would meet some of the same photojournalists who inspired him and have the opportunity to work with them.

As soon as he finished his undergraduate studies, he went to his native Chile. There he met Hugo Infante, who had been a photojournalist during the 2004 Iraq war. Infante became Ortega’s mentor and taught him how to create a good news photo.

“I knew how to make a picture and write a story, but I had to learn how to put those things together by myself,” Ortega said.

Infante and Ortega worked together to cover the Chilean earthquake in 2010 and later in October the miner’s rescue.

They arrived at the site three days before the actual rescue to see the Chilean president staring down a hole in the ground. That photo would later be used on the rescue site.

During the rescue, Ortega didn’t get to sleep because once the first miners were pulled to the surface, the rest of the miners were pulled up at an increasingly faster pace.

He had about three minutes to process photographs of each miner, running from the rescue site to a trailer acting as the communications office, plug in the CF card, find the images, caption them individually and upload them to Flickr.

There was no time to set up a server that could handle all the media attention. Flickr found out about the situation because of the amount of traffic the account was getting and highlighted the photos on their main page.

News organizations across the globe were using Ortega’s photos with their stories of the international event.

After reading the book “Deep, Dark, Down,” Ortega learned the rescued miner’s stories.

“It was really cool for me to understand the stories of these people, because for me at the time it was very superficial,” Ortega said. “I just saw miners coming out of a tunnel who were immediately sent to the triage where they were doing all kinds of medical exams.”

His experience there was one many photojournalists work their entire careers to have.

Photojournalist Kael Alford, who teaches news photography at Eastfield and Southern Methodist University, said Ortega’s work with the miner rescue was invaluable.

“When you get one of those news stories that gets a lot of attention, you’re suddenly catapulted into this platform,” Alford said. “That’s something that’s hard to come by as a journalist, which is a big microphone.”

Alford met Ortega at one of the first Foundry Photojournalism Workshops, a now-prestigious annual event, in 2008 in Mexico City, where Ortega was a workshop producer and social media coordinator. He also worked as an assistant instructor for the “Heart of Mexico” international journalism study abroad class through the University of North Texas

Ortega earned his Master of Journalism from UNT in 2013.

Ortega experienced one of the most touching moments of his career working for the UNT Mayborn Magazine.

He was covering a story on hillbillies in Tennessee, accompanied by Nickell, the journalist he worked with on the Kachin story. This was their first assignment, retracing the steps of photographer Joe Clark.

[READ MORE: “Close-Up Magic” challenges definitions of fine art]

Their main goal was to find a young boy named Jimmy Powell, whom Clark had photographed. Ortega and Nickell made phone calls and traveled the same path Clark had, photographing their journey.

After a week of searching, Ortega and Nickell found themselves in a small, run-down town. There, Ortega found a chain-smoking, half-drunk man wearing a dirty letterman jacket with a brown-bagged beer in his hand. The man came out of the train station and approached journalists, snarling at them, asking what they were doing.

Rather than leaving, Ortega and Nickell began to talk to him. They learned he was wearing his son’s letterman jacket. The letterman jacket was the only item salvaged from the car crash that killed his son.

In talking to him, Ortega learned that the man and his partner had turned the train station into a squatter’s home.

“After we established trust with him, he invited us in and told us his story, and that was really touching,” Ortega said. “So I did this portrait of him and his partner in front of this building. I was able to get the shot I wanted, but even better — with the human element.”

Alford appreciates Ortega’s work because she sees that he gets close to his subjects.

“He has an understanding that intimacy in a story and getting close to your subjects is an important part of storytelling,” Alford said. “It’s not just about being in the right place at the right time but also understanding your subjects and learning as much about them as possible. When he gets a big story or a project, he gets as close as he can and spends a lot of time with the people that he is photographing. I think that’s probably the most unique thing about a photographer like Morty.”

Being a freelance photojournalist means having to find a story and sometimes go out on a limb, Ortega said. It can be dangerous and for many, it is hard to get stories published. In many cases, Ortega would pitch his story to multiple editors and nobody would pick it up.

“It’s either feast or famine,” Ortega said. “You could go weeks without work or you could have a really good month where you have up to three assignments and get well paid for it.”

Because of the difficulty in the field, many photojournalists have side jobs as event photographers or, in Ortega’s case, as teachers. Ortega worked as an adjunct news photography professor at Eastfield for two semesters in 2016-17, in part to raise money to finance future stories.

Ortega regularly invited guest speakers to his class, including freelance and portrait photographer Jeremiah Stanley.

Eastfield graduate and professional photographer Alejandra Rosas connected with Stanley through Ortega’s class and had the opportunity to work as his assistant on an assignment.

Although Rosas had a digital photography certificate and a lot of experience, she said she found the class valuable.

“It felt like I was learning photography again,” Rosas said.

Rosas said one of the things that made Ortega an interesting professor was his experience photographing international news like the Chilean mine collapse and rescue.

“You see it on the news and everywhere, but you never imagine you’re going to meet somebody who was there,” Rosas said.

Ortega now works for the marketing team for Baylor University. He makes videos, has a stable income and a home in Waco with his wife, Madiha Kark.

Even in his current job, he works with people to visually tell their experiences and stories.

“It’s really about the world, less about one self, so that’s something I really liked about photojournalism,” Ortega said. “The capacity to connect with the world.”

Editor’s note: The narrative introduction originally placed Ortega in the back seat and stated that journalists traveled at night. These were incorrect and have been updated to reflect the true events. The Et Cetera regrets this error.

https://eastfieldnews.com/2018/01/30/choir-student-overpowers-mental-illness-with-music/