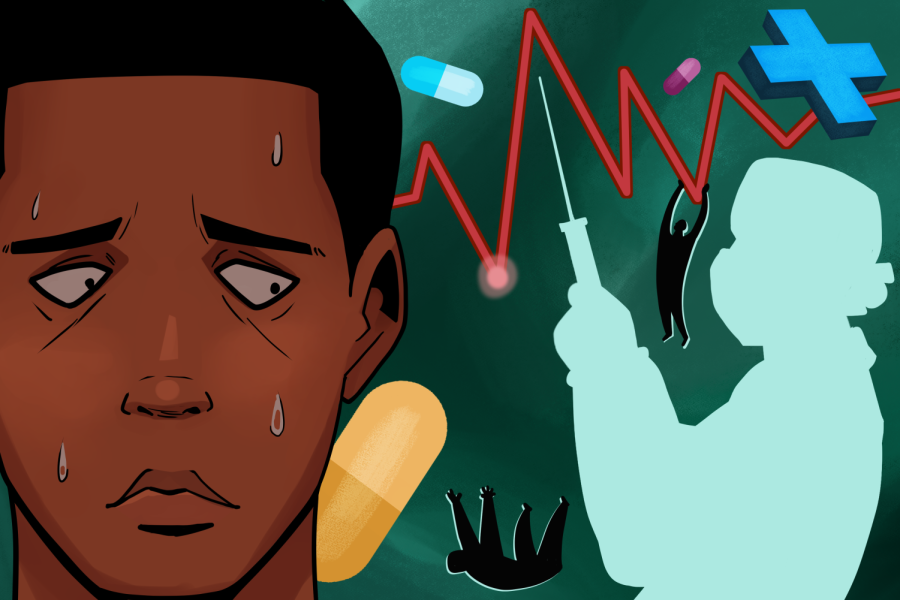

OPINION: Health care’s racist past still harms patients today

February 28, 2023

Despite the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention raising over $156 million in funding to ensure that everyone got vaccinated, only 44.1% of African Americans were fully vaccinated by the end of 2022 as compared with 59% of non-Hispanic white people.

The COVID-19 pandemic affected everyone, but some groups felt the impact more significantly. Children, disabled individuals and the elderly were among those with the highest mortality rates. But once the distribution of vaccines began, minorities were left behind.

The lack of access to vaccine facilities and priority distribution among neighborhoods were blamed for the imbalance, but a lack of trust in medicine caused many people of color to not participate in getting the vaccine.

“Incidents of the medical establishment endangering the health or betraying the trust of Black patients and research participants have complicated the relationship between the medical establishment and these communities,” according to an article published by Johns Hopkins Medicine.

At the beginning of modern medicine, many doctors believed that darker skin was thicker, and therefore resulted in higher pain tolerance than those with less melanin.

This concept is seen in many medical books, including “Nursing: A Concept-Based Approach to Learning.”

The book originally contained a section in which it described the “cultural differences” between different races of people.

This section was removed in 2017 because of the harmful rhetoric that described African American, Hispanic, Asian and Jewish people.

A 2018 study by Kaiser Permanente’s Dr. Fatu Forna about maternal death of different ethnicities revealed that “in the U.S., Black women have three times the maternal mortality rate of white women.”

Possible racial bias by medical staff minimizes the experiences of pregnant women of color. This includes ignoring a patient’s concerns, questions and expressions of pain.

These experiences can cause many to not seek care out of fear of not being heard.

This fear is justifiable when you consider that “the father of gynecology,” J. Marion Sims, developed his surgical techniques through painful experimentation on Black slaves.

This same inhumane treatment of Black women was seen in the 1950 birth control trials in Puerto Rico. Biologist Gregory Pincus exploited poor women, coercing them into taking pills and then ignoring the side effects.

My mother was also a victim of medical malpractice. Forced to have an abortion due to domestic abuse, fragments of tissue were left inside of her. When she expressed concerns about bleeding and nausea, she was dismissed. This put her in shock, and she could have died.

Many other women of color have experienced this, and the consequences can range from infection to death.

There is an obvious need for medical re-education. All doctors, nurses and other health care workers should submit to unconscious bias training. This would ensure that they will treat everyone with the same consideration. Medical textbooks should also be examined, and all harmful stereotypes eradicated.

Progress will come from examining the health care statistics of people of color, like Forna acknowledged, and then holding providers accountable. We have a long way to go as a society, but it is our job to press for change.