Eastfield’s Buried History: Exploring the Motley Cemetery lore

The Motley Cemetery. Et Cetera file photo.

November 9, 2018

The Motley family, which migrated to Texas from Kentucky, purchased the land that is now Eastfield College in 1865. While the families vacant home, the Motley mansion, burned down in 1967, Eastfield college was established in 1970 and the family cemetery remains on the campus. Read the stories of four family members who were buried in the Motley Cemetery, and the foot that was buried there too. —Compiled by Aria Jones

Click the links below to read:

First grave: Penelope “Penny” Motley

The civil war soldier: Francis Marion Motley

One foot in the grave: Grover Cleveland “Cleve” Motley

Cemetery repair: Joe Bailey Motley

By SAMUEL FARLEY

@SamFarleyETC

The Motley family cemetery is a unique part of Eastfield, where generations of pioneers and their descendants lay at rest beneath brown and gray headstones enclosed by a milky-white iron fence. While the imposing grave of the family’s patriarch, Zachariah Motley, stands tallest amongst his family, there is one grave that stands apart from the rest. That is the grave of Penelope Ann Motley McLain, who is the reason why the cemetery was built.

Penelope was born June 14, 1842, in Allen County, Kentucky, to Zachariah and Mary Lynn Motley. She was the third oldest child among her 10 siblings. Her father Zachariah was a successful farmer and businessman who brought his family to Texas during an uncivil time, according to descendant and family historian Carol Riggs Anderson.

Anderson has spent years knitting together her families’ histories through pictures, reunions and court documents. She calls Penelope “Penny,” and though Anderson never met Penny face to face, she has taken the responsibility of passing down her family’s history to heart.

Anderson sits at a family dinner table with tintype photographs of old family members displayed on the walls behind her. She speaks about the wagon train that Zachariah used to bring his family and other settlers from Kentucky to Texas in 1856.

“Penny was 14 years old when Zach brought the family to Texas,” she said. “In those days, if you were old enough to walk outside the wagon you did, so she walked most of the way. She was one tough girl.”

From Bowling Green, Kentucky, the family began their journey to Dallas. The distance is over 700 miles. Anderson believes that the reason the family traveled so far was that of the turbulent times that the Motleys were living.

“Bleeding Kansas, that’s what brought me here,” Anderson said. “Zach owned a family of slaves, so he figured that it was best to move his family and slaves to Texas where they would be safe.”

Bleeding Kansas was a conflict that started in 1854 between anti- and pro-slavery groups in the newly created state. Violence broke out in the territory, and it became dangerous for owners of slaves who lived in the area.

“Zach didn’t own a lot of slaves,” Anderson said. “There was a father and mother and some children, but I think what happened in Kansas made him fear that people in Kentucky might start up the same thing.”

The total land acquired by Zachariah was over 6,000 acres and included parts of Mesquite, Garland and Dallas. Penny married J.B. McLain in 1861 at the age of 18 at their home in Breckenridge. McLain was a captain in the Confederate Army and was away from home when Penny gave birth to their son J.B. McLain Jr. in 1862. According to family lore, Zachariah began construction on the family’s farmhouse in early August the next year when Penny and her son fell ill.

According to Anderson, their deaths were the result of an epidemic such as typhoid or pneumonia.

“In those days illnesses turned into epidemics quickly because people didn’t have the medicine that we have today,” Anderson said.

Penny was buried in December of 1863. She was 21 years old and the first of the family to be buried in the cemetery. A few months later, J.B. Jr. passed away.

Both Penny and her son are examples of the hard and fragile life that pioneers lived. J.B. McLain Sr. survived the war only to find out that his wife and son had passed away. He sold his land to Zachariah and according to Anderson, “went home.” Although his home is unknown, it is believed that Mclain was from Kentucky.

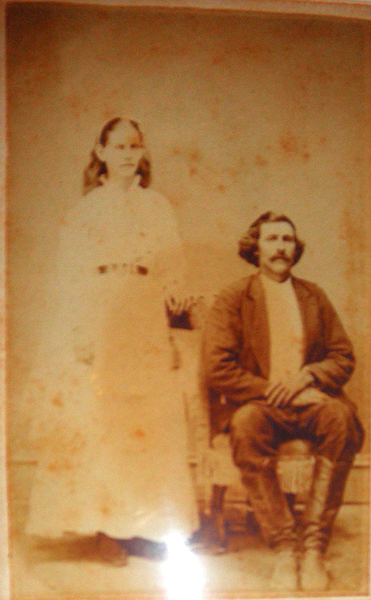

There is only one surviving picture of Penny and her husband. She stands next to a sitting J.B. with her hand placed on the shoulder of his chair and her eyes gazing off into the distance.

Like the picture, Penny’s life was brief like a snapshot of a much larger story. And yet 155 years after Penny’s death, the Motleys and their extended family are continuing the tradition of being buried in this cemetery.

By JAMES EYRE

@JamesEyreETC

A covered wagon rides along a bumpy, dusty road. A man and woman, their 10 children, and a family of slaves brace themselves for a trek from bloodshed in Kentucky to safety in Texas. Those who could walk, including the children, walked alongside the wagon.

Francis Marion “Frank” Motley was one of them.

Frank, the fifth of 10 children to Motley patriarch Zachariah and his wife, Mary Lynn, was born Sept. 22, 1844. He was a mere 12 years old when this caravan began.

During this time, Kentucky was a “border state” between the slave-owning South and free North. The Motleys left Kentucky, trapped in a war within a war, for Texas so they could keep their slaves, all of whom were from the same family.

At the start of the Civil War, 18-year-old Frank and his brothers William and Jefferson served in Company K, 19th Texas Cavalry Regiment at Camp Stonewall Jackson. Many of the men were recruited from the North Texas area.

According to Motley family historian Carol Anderson, no surviving photos of Frank exist. He is described as being 5 feet, 7 inches tall with fair-colored hair and gray eyes in a document she provided.

Company K was involved in Gen. John S. Marmaduke’s Missouri Raid of 1863. Nine in the unit went missing, 19 were wounded and five killed. The cavalry also fought in operations against Banks’ Red River Campaign the following year. The campaign, led by the Union, set out to capture everything along the Red River in Louisiana and Texas.

When the war ended in 1865, the cavalry disbanded, and Frank joined the Texas Rangers Division for a brief period that same year.

“He had to provide his own horse, his own tack, and they didn’t pay him very much,” Anderson said. “It was very brief. He did six weeks to six months.”

Afterwards, he returned to his family’s land and continued work as a cotton farmer.

Frank married his first wife, Isabelle Williams, in 1868. The couple had six sons: Thomas Zachariah, Benjamin Franklin, William Masten, Charles, Hugh Richard and Delbert, and three daughters: Edna, Gussie and Hattie.

Isabelle died in childbirth with daughter Hattie in 1894. Frank later married Mollie [records did not reveal her maiden name]. They had no children and remained married until his death.

According to Mesquite city librarian Molly Allison, Frank’s daughter-in-law Bess was a schoolteacher and librarian who contributed to the creation of the Mesquite Public Library system in 1939.

Anderson said Frank was highly religious and donated land for an early church located on what is today Gus Thomasson Road in 1894.

He died of natural causes June 14, 1915, at the age of 70 and is buried in the Motley family cemetery with his first wife, Isabelle, buried to his right and his second wife, Mollie, buried to his left.

By ARIA JONES

@AriaJonesETC

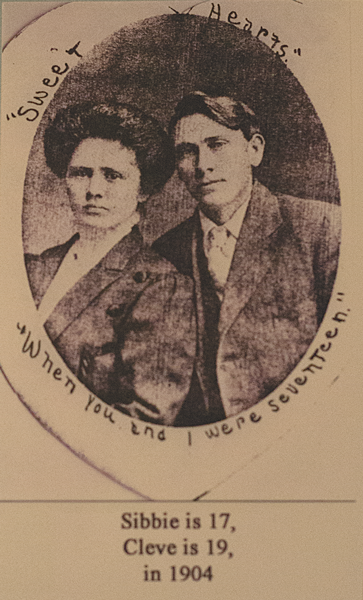

Grover Cleveland Motley broke his foot beyond repair when he was thrown from a horse, or a pig, as some family believe. After being amputated and buried in 1911, the foot shares an address with Eastfield College at the Motley Cemetery.

“He was ridin’ like a fool,” Motley family historian Carol Riggs Anderson said. “The horse got away from him, or he fell out of the saddle — I’m not sure what it was — and drug him.”

Anderson, a relative of the Motley family, said then 26-year-old Grover Cleveland Motley, or “Cleve” as the family called him, had a mangled foot. But he managed to free himself from the stirrup and get back home, where the family took care of him.

Cleve’s nephew, Bobby Poynter, said he remembers the story much differently. It’s possible Cleve was horsing around.

“The family story that I know is that he was riding a pig,” Poynter, 84, said. “Now maybe someone said he was riding a horse. He may not have supposed to have been riding a pig. I can visualize him doing that.”

Anderson said the doctor was called in when the foot wasn’t recovering. “The doctor said, ‘You’ve broken every bone in your foot and it’s now gangrenous and it has got to go,’ ” she said.

Cleve’s foot was amputated above the ankle and buried in the cemetery near the Motley mansion.

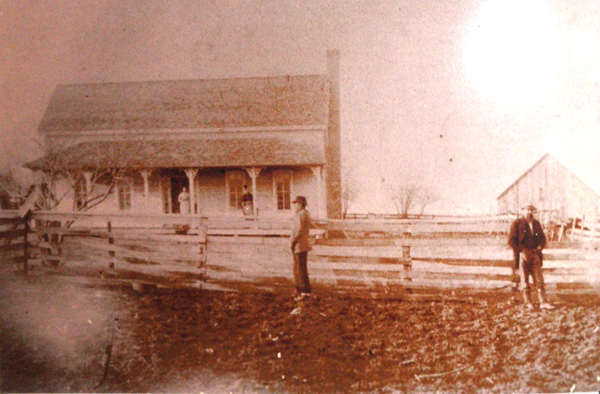

Established in 1857, the mansion was built when Cleve’s grandfather, Zachariah Motley, bought 320 acres of land. That land went on to be used as a homestead, farmland, a golf course and eventually Eastfield College after it was bought by the Dallas County Community College District for $970,552 in 1966.

After his amputation, Cleve was outfitted with a prosthetic and took over the home on the property until 1955, when he moved to a new house on Shiloh Road. The mansion included 10 bedrooms, a wrap-around porch, and a red roof that Anderson said could be seen from downtown Dallas at one point.

The Motley mansion stood on the site of the current Eastfield College campus for 88 years, and Cleve watched over it for 43 years, nearly half of that time. Poynter said this was where many of the family get-togethers were when he was a child, and that most of his memories are from when he was 10 years old or younger.

Cleve farmed his whole life until he retired. Even on his World War II draft card, his profession is listed as farming. The farm was primarily used to grow cotton and corn, but Poynter said there was much more.

Poynter said the farm had mules, pigs, chickens and other livestock. He said he remembers the farm having bees for honey and an orchard to grow peaches, plums and other fruits to be canned.

“When I got big enough to start helping on the farm, they were still using mules to farm the land in the ‘30s,” he said. “Starting in the ‘40s we got tractors.”

Poynter said Cleve was someone who liked working with his hands. He had several mules to work the farm, along with horses and blacksmith equipment to make their shoes.

“He was a grouchy fella,” Poynter said.

He said Cleve was like many of the men he remembers from that time: tough. But he still got along well with most people. The reason, he said, is because Cleve had to be a hard-to-deal-with businessperson. That’s how men made their money.

“Nowadays it’s not like that,” he said. “But back in the (‘40s and before), that’s the way it was. It was a rugged country at that time. Back then, you had to be that to survive.”

Poynter said most of the roads were made by landowners with packed dirt and gravel, and the Motleys purchased property that would provide the gravel and fence posts they needed.

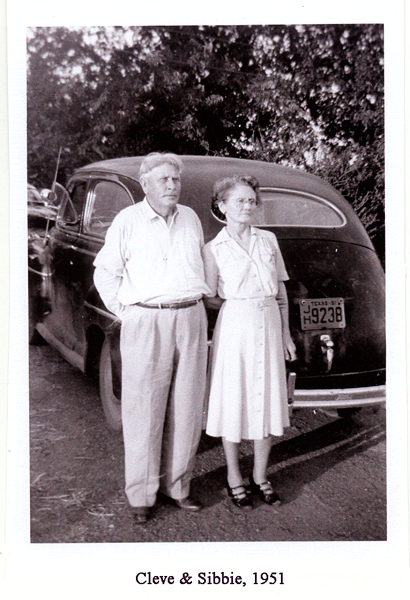

While Cleve is described in a children’s book, “Motley Mansion Part II,” as being a bachelor with little patience for kids, he was married to his wife Sibbie for 66 years until she died in 1971. The couple never had children. But Poynter lived next door and remembers Cleve not wanting children on his property, worried that they might take fruit from his orchard.

“He was always concerned that we were getting his pears and he’d say he didn’t want us bothering those pears,” he said.

Although the pears were on the fence line, Poynter said he didn’t have any reason to take them. His family farm next door had pears, too.

“I just know that if he had kids, he wouldn’t have worried about who got his pears,” he said.

Cleve’s final resting place is not with his foot, but by his wife’s side at Grove Hill Memorial Park in Garland. He died in 1977 at the age of 92.

Anderson said it was never even Cleve’s decision to bury his foot. It was his aunt Sallie Motley who made the decision in 1911 to bury it and keep the animals away from it.

Poynter said one of the reasons he may have chosen not to be buried with his foot is that the property ownership of the cemetery moved to the Lawrence family, who intermarried with the Motleys. That meant there was no way to ensure the future of his grave.

In the children’s book, Cleve said, “I don’t care if you cut off my foot. As long as you promise to bury it next to the arm grave.” And there is an arm buried in the cemetery. John S. Motley, Cleve’s cousin, lost his arm in a cotton gin accident in 1894.

By Colin Taylor

@ColinTaylorETC

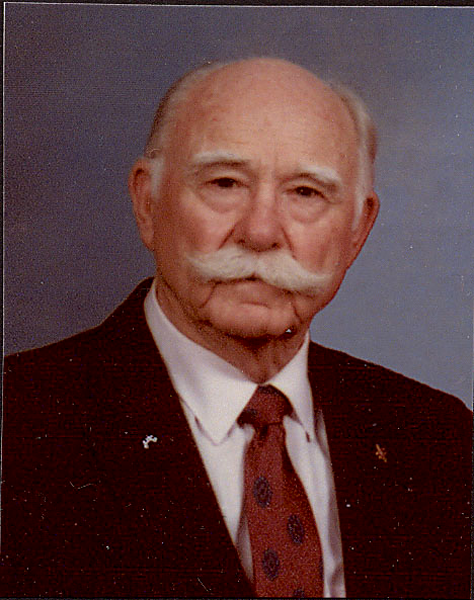

By the ‘60s, the Motley Cemetery was more than a century old, and someone had to continue caring for it. That person was Joe Bailey Motley, who served not only the cemetery but also the community.

“In a family effort to restore the cemetery which had gotten in bad shape, the fence was taken down, repaired and re-installed,” said Joe Bailey in a 1988 edition of the Mesquite News.

As the caretaker of the family cemetery, in 1968 Joe Bailey not only restored the cemetery, but also expanded the cemetery. Included in the expansion were new grave markers for the slaves that were buried nearby.

Previously marked by short wooden posts, Joe Bailey replaced the posts with bronze plaques that read “Known only to God.”

Not only did he include the family’s slaves in the cemetery, he also included an odd plaque for the arm of his father, John Stephen Motley.

John lost the arm in 1894, during an accident at the cotton gin where he worked. His right arm got caught in the machinery and when he was dislodged, his arm was “held to his body only by sinew” according to Joe Bailey. After being brought to the owners of the gin, the Heart family of Reinhart, Texas, doctors decided to amputate the arm.

The family later buried the arm in the cemetery.

“They couldn’t throw it out for the birds to peck and they couldn’t burn it,” said Joe Bailey in the interview with Valerie Barna of Mesquite News. “We had the cemetery right near the house, it was just logical to bury the arm in the cemetery.”

According to family legend, John began experiencing a phenomenon known as phantom limb. Phantom limb is when an amputee experiences pain felt in a limb that is no longer there.

John started complaining that it felt like ants were biting at his arm. The family dug up the arm and found it covered in ants. They re-buried the arm in an airtight box.

John died in 1925 but was not buried with the arm, instead he was buried in Grand Prairie.

Not only did Joe Bailey restore and expand the family cemetery, he also financed for the cemetery to become a Texas Historical Marker in 1976.

Joe Bailey was no stranger to service.

Graduating from Garland High School in 1936, Joe Bailey worked at Luscombe Aircraft in Garland. In 1942, he enlisted with the U.S. Coast Guard, serving for more than three years.

In 1941, he joined Garland Lodge #441, where he would eventually achieve the most senior officer position, Worshipful Master, in 1952. He would hold the position, as well as treasurer, for more than 20 years.

“He is the standard we all try to live up to,” said Eric Stuyvesant, a member of the Garland Lodge. “To live humbly, to our service community, to our fellow man, to do good in our world.”

Stuyvesant did not know Joe Bailey personally, but knows the impact left for all future members of the lodge.

“Any time a new member comes in, they are taught first about Joe Bailey,” Eric said.

He was a charter member and organizer of the Duck Creek Masonic Lodge #1419 and a member of the Dallas Scottish Rite Bodies, York Rite Bodies and St. Mark’s Conclave of the Red Cross of Constantine.

He served on the Garland I.S.D. Board and the local draft board. In 1986, he chaired a committee to build a recreation center, later named the Joe B. Motley Recreation Center.

He told the board not to name the recreation center after him. Without consulting with him or informing him of the decision, they named the recreation center after him anyways, according to his obituary in the Dallas Morning News.

“Joe Bailey was a very civic-minded person,” Carol Anderson, family historian and descendant of the Motleys, said, adding that he was a “wonderful man.”

Joe Bailey was married for 68 years to his high school sweetheart Dorothy Range, who died at the age of 97 in 2015. Although they lost their daughter Marilyn, who died in 2002 at the age of 52, they are survived by their daughter and son-in-law, Molly and Mark Grant.

His obituary says that he was “a humble and modest man who never sought attention for himself, he never tired of helping others.”

Tyra Newkirk • Aug 30, 2022 at 5:07 pm

Very interesting I remember when the structure burned. I also recall the cematery as it looked before the College was built. My parents knew some Motley family and I remember one of them taking me for a horse ride as a child. We lived across the street that was named for the Motley family. I enjoyed this article. I learned so much from it and I Thank you for shareing the story.

Charlie Smith Davis • Aug 29, 2020 at 12:29 pm

Yes, my grandmother was a Motlry, but was disowned because she married a man the family did not approve of.