Seeing green: History professor Matt Hinckley saves money and helps protect the planet through environmentally conscious decisions

September 9, 2020

By SKYE SEIPP

@seippetc

“Do you ever think we’ll be the last generation of kids?”

This wasn’t an existential crisis. Just a question posed by one 11-year-old to his sisters while playing a video game months before anyone had heard of COVID-19.

“That’s some heavy shit,” history professor Matt Hinckley said in a drawn-out, low breath after recalling the conversation he overheard between his son, daughter and step-daughter.

“For an 11-year old, ya know? I…”

He stopped himself from talking. He averted his eyes, turned to face the window in his office and regained his composure.

He sat silent for 10 seconds.

“I can’t be complicit in this carbon-based system anymore,” Hinckley said.

Overhearing this conversation didn’t cause Hinckley to power his home with 31 solar panels. That realization came from a trip he took in June 2019 as a part of his “50 by 50” goal, where he wants to travel to all 50 states by the time he turns 50. He has two more states left: Idaho and Hawaii. He had planned to visit Idaho this summer, but those plans were thwarted due to COVID-19.

On his last trip, Hinckley along with his wife, kids and an exchange student drove through the power-supplying states of America: Wyoming, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota.

541 million years ago this was an ocean. Fossil remains of sea creatures can be found scattered across places like Green River, Wyoming. The vast empty plains, rolling hills and big skies of these states make it feel like you’re driving a submarine. For most of the United States, these fossils are how the lights turn on.

Hinckley had already begun thinking about going green and had purchased his electric car, a Chevy Volt. He wanted to save money by installing his own solar panels on his suburban home in Sachse, so he began taking renewable energy classes at Eastfield.

But his plans accelerated after seeing the continuous cycle of trains pulling carts of coal across the strip-mined Western plains.

“That trip convinced me to just … do it right now,” he said.

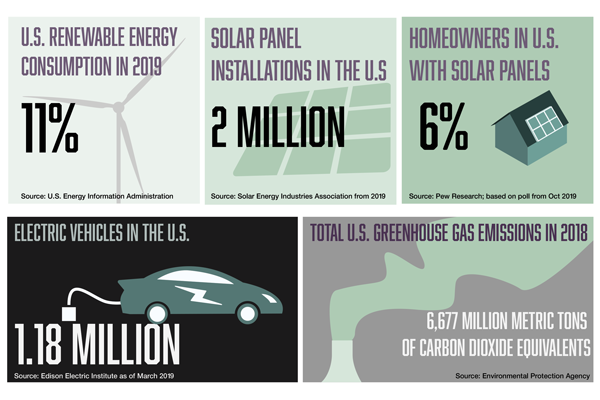

He no longer wanted to contribute to the endless amounts of energy produced by burning fossil fuels. In 2018, the United States produced 4,171 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity. Only 17 percent came from a renewable source such as wind or solar energy.

Almost 80 percent of America’s energy needs that year came from burning fossil fuels, which release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere and create a blanket over the Earth. It forces heat to get trapped, which ultimately causes the greenhouse effect, and leads to rising oceans, extreme weather conditions, drought, famine and the displacement of people around the globe.

“We humans are the architects of our own extinction,” Hinckley said.

‘Do our part’

Hinckley had the solar panels installed to help do his part in cutting down his carbon footprint, but the expenditure came with additional benefits.

His electric bill on Feb. 22 was -$19.17, which means the utility company owed him money at the end of the month. But during the summer months he ends up with an actual electric bill from running the air conditioning system in his house.

It’s not a cheap investment, but for Hinckley, it had to be done. Time is of the essence.

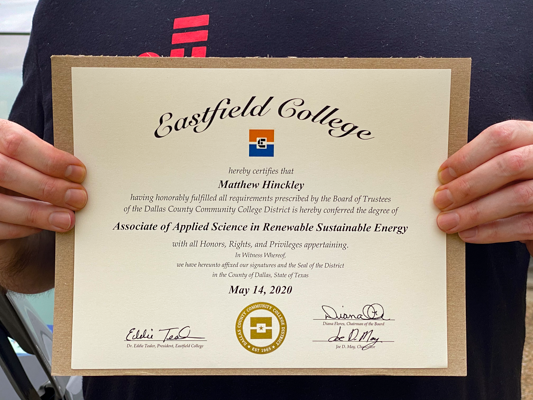

In November of 2018, he was diagnosed with cancer. It’s gone now. But it was after this run-in with his own mortality that he bought his Chevy Volt and began studying renewable energy with mechatronics professor Arch Dye. He received an associate’s of applied science degree in renewable energy this summer and was one of the last people to earn the degree which was discontinued after August.

Cancer isn’t the only health problem he’s faced. At 21 he was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in his small intestine. He missed his college graduation because of it.

It’s now spread to his face. And living with Crohn’s disease today means he is immunocompromised and has to be extra cautious not to catch COVID-19.

Other than occasional trips to the grocery store or picking up his kids, Hinckley said he is staying inside to avoid exposure to the coronavirus.

“I’ve always been extra careful,” he said. “I’ve always been a meticulous hand washer. I don’t typically get myself into a lot of crowds anyway. The biggest crowds I regularly interacted with was my classes.”

He’s also had problems with asthma and allergies his whole life. In November 2016, he decided to have surgery on his septum to try and fix the problem.

As he awakened from the surgery, he drew a deep breath through his nose and said, “I can breathe.”

That’s when the anesthesiologist standing next to him cut in.

“You’re breathing really well not because of the surgery, but [because] we gave you a really strong decongestant,” the anesthesiologist said.

“What are you talking about? I can breathe,” Hinckley responded.

“Well, we didn’t go through with the surgery.”

“Why not?”

“Well, after we administered anesthesia and we intubated you, your heart stopped beating,” the anesthesiologist said. “ And we had to administer epinephrine through the IV to restart your heart.”

He died for a few seconds. There was no white light or tunnel. He didn’t even know it had happened.

His death was caused by the intubation process, which is when a tube is run down your throat. It triggered a nerve in the throat muscle which can sometimes cause the heart rate to slowly decrease.

“Sometimes I like to joke that Trump had just got elected and my heart couldn’t go on,” Hinckley said, laughing.

Since his election, Trump has pulled the United States out of the Paris Climate Agreement and his administration has completed 68 cuts to environmental regulations. The administration is in the process of rolling back another 32 as of August 2020, according to a New York Times analysis. The most recent act of deregulation on Aug. 17 will allow oil and gas companies to drill on over 1.5 million acres of coastal plains in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge.

A study by the New York University School of Law in March 2019 said these cutbacks could have dire consequences on climate change and the health of individuals.

Hinckley knows his actions won’t solve climate change, but that doesn’t stop him from continuing his efforts.

“No one of us is going to save the world, but we could at least do our part to slow down the decline,” Hinckley said.

Humble roots

Hinckley is not only a leader in embracing the green lifestyle. He is also the newest Faculty Association President, a position he has held two previous times in his tenure at Eastfield. He is also an outspoken advocate for the one college initiative.

Hinckley didn’t always want to be a teacher. He grew up in Mokena, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago and he aspired to be a pilot at age 15. His favorite plane is the SR-71 Blackbird, a spy plane built during the Cold War that to this day holds the record for being the fastest manned airbreathing jet engine at 2,193.2 mph. A plastic model sits on top of the bookshelf in Hinckley’s office.

He knew the military wasn’t an option for him. He didn’t have the discipline, and with asthma, he wouldn’t have made it past basic training.

His dad was a dean of the industry and technology programs at Moraine Valley Community College. When he was 16, he took a Western Civilization history class at the college and decided he wanted to teach history at a community college.

Around this time, he learned about human-induced climate change from a documentary on PBS.

He graduated from high school in 1994 and began taking classes at Moraine Valley, where he worked for the student newspaper, the Green Valley Glacier. After two years, he transferred to the University of St. Francis in Joliet, Illinois, a city most famous for being home to the prison that Jake Blues was released from in the 1980 film “The Blues Brothers.”

During his first semester at St. Francis, he worked for the Desplaines Valley News, where he was hired as a reporter and also did some photography and page layout for the weekly suburban newspaper.

He graduated with a degree in history in May of 1998 from the hospital. It was during this trip due to sharp stomach pains that Hinckley discovered he had Crohn’s disease.

After six months without having the job he wanted, he called up his Aunt Sue, who lived in Allen. She told him to come down to Texas, so he did, on New Year’s Eve.

By the fall of 1999, he used the skills he gained as a journalist and began working at Richland as a student media adviser. In 2004, he earned his masters from the University of Texas at Dallas, and in 2008, he started working at Eastfield as a history professor, his dream job.

Continuing his efforts

With his ideal job now secured and a supportive wife, Hinckley has been able to invest in his green initiatives.

A single solar panel can produce over 300 watts of power. With the 31 panels Hinckley owns, he can produce up to 930 kilowatts of power a month.

For the month of February, he bought $80.75 worth of wind power from the grid but sold $98.43 worth of power to the grid.

He estimates his system — which he paid roughly $26,000 for — will pay for itself within five years. The panels also come with a 25-year warranty and a federal tax incentive that took nearly $7,800 off of the total cost.

“I’ve got free power for the next 25 years,” Hinckley said.

The photovoltaic panels convert energy from the sun into DC electricity. This is then sent to an inverter, which turns the electricity into AC current. That power is used to power homes and sent to the grid.

Hinckley said everyone, including himself, can do more to reduce their carbon footprint.

“Not everybody can afford an electric car, not everybody can afford a set of solar panels … but you could grow tomatoes in a pot,” he said. “Those of us with a little more privilege, with stable careers, maybe that means you don’t take a vacation.”

In his backyard, Hinckley has a small compost pile of ripped-up Amazon boxes, leaves, fruit and vegetables. He laughed at the irony of his use of Amazon packaging but said at least he’s doing something with the boxes.

Last year, he and his wife started a small garden with plants like tomatoes. When the coronavirus pandemic forced him to work from home, he bought a hydroponic garden and is expanding his growing capabilities with basil, kale and swiss chard.

He’s almost cut out all beef from his diet, unless it’s grass-fed, and orders bison from Wyoming. Hinckley said this type of meat isn’t produced in a factory farm and the bison are able to graze freely on grass, unlike a lot of beef that’s pumped with hormones and fed a diet of corn and soybeans.

Another future plan of his is to insulate his attic better so his heating and air conditioning system can operate more efficiently.

In Texas, a lot of these systems are put in the attic. The unit pulls in air, which in the summer can be extremely hot, and converts it to cool air. Being in the attic requires the system to work harder in the summer months, ultimately causing more power to be used and decreasing its lifespan.

His hope is that some of these energy-saving practices can be carried over to Eastfield. Rather than having roughly 240 acres of unused grass, the school could start planting vegetable gardens, which he said would help students who are using services like the mobile food pantry. He added that the pantry could also stock and distribute LED lightbulbs.

Looking back on the question he overheard from his son, Hinckley said his childhood was easier than that of his own children.

He grew up in a time where the biggest fear was the possibility of mutually assured destruction but said overall it was a simpler time. One that was spent riding around town on his bike to pick up groceries for his mother.

“Did I have a privileged childhood? Sure,” Hinckley said. “[But] I didn’t have to worry about ‘are we going to be the last generation of kids?’”