By JORDAN LACKEY

@TheEtCetera

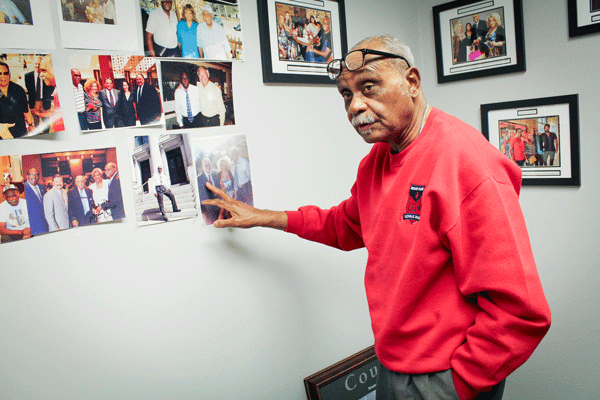

The Rev. Peter Johnson stood behind Martin Luther King Jr. at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial during the March on Washington, Aug. 28, 1963.

Johnson, then a college student at Southern University in Baton Rouge, had led the Louisiana delegation across the south to the nation’s capital to protest inequalities faced by African Americans.

The sky was clear, but his mind was clouded, troubled by the turmoil he’d witnessed on his journey. He was unable to truly appreciate the magnitude of the situation transpiring just a few feet away from him as King addressed the crowd.

King was about halfway through his speech when he looked back and over his shoulder at gospel singer Mahalia Jackson.

“Martin!,” she shouted. “Tell them about your dream, Martin!”

King closed his leather binder, put both hands on the podium and leaned back like an old preacher.

“Dr. King is getting ready to take us to church now,” King’s chief of staff, Wyatt Walker, whispered in Johnson’s ear.

Then the powerful words “I have a dream,” boomed through the National Mall.

Those words wouldn’t be taught in schools today if it wasn’t for Jackson’s loud voice and influence, Johnson said in a recent interview.

“That wasn’t supposed to be a part of that speech,” he said.

It became one of the most famous orations in history.

Johnson has been an activist in Dallas since moving here in 1969. He teaches at the University of North Texas and will speak Feb. 12 at Eastfield for Black History Month.

As a student leader at one of the largest black schools in the country, Johnson was often responsible for gathering student protestors.

“Everyone depended on the students,” he said. “The students were the foot soldiers of the civil rights movement. Without students, you can’t have a civil rights movement.”

He said it was no big deal to gather eight busloads of students at any given time.

“They didn’t want to go to class anyways,” he said laughing.

After several senior community leaders were put in jail due to civil disobedience, including the principal and pastor of his hometown, Plaquemine, Louisiana, Johnson became solely responsible for organizing the state’s delegation for the March on Washington.

Johnson said the participants made a pact not to follow “the American apartheid system.” If they encountered “black” or “white only” signs, they would purposefully use the wrong facility. He said the biggest problem was finding money to bail them out of jail afterward. The day of the march, that responsibly weighed heavily on his conscience.

“It fell on the shoulders of the students to organize the Louisiana leg of the march on Washington,” he said. “Between Louisiana and Washington, D.C., I had kids thrown out in jail all over the South, because every time we stopped somebody went to jail.”

During his visit to Eastfield, Johnson plans to speak about the importance of voting and appreciating the sacrifices made to attain that right.

“Most of us shed blood for the right to vote,” Johnson said. “It didn’t come easy. It took years and years. …The right to vote has a long, sacred, bloody history for us. … I’ve got friends in the graveyard for the right to vote. … The right to vote is stained not just with blood but with funerals.”

Johnson said this mentality applies not only to federal elections, but state and local elections as well. History professor Liz Nichols, who teaches an African American history course, agreed.

“It’s not that the presidency is not important,” Nichols said. “But sometimes we’re just so far removed from what happens at the federal level, you need to kind of concentrate on what’s happening in your state. Who’s running your state, and who’s running your city? … Study the issues, look at some objective or multiple sources and make an informed decision.”

Brynndah Hicks Turnbo, co-chair for this year’s Black History Month committee, played a crucial role in booking Johnson to speak.

“When I saw the theme was African Americans and the Vote, I really got excited about it because it’s an ongoing history lesson for us,” she said. “We were looking for a walking history book. That’s how we came about finding the reverend. … He has an incredible story to tell.”

Hicks Turnbo hopes this month’s events will educate and inspire people to get out and vote.

“It’s an ongoing job having to determine what is important,” she said. “Or how to bring awareness to an issue that may never cross our minds until it is humanized and bleeds into the heart of our conscience.”

Johnson originally came to Dallas to plan the premiere of a documentary about the works of King and to help raise money for the King family shortly after his assassination. The assignment was expected to last a few months, but after being asked to help Fair Park residents get fair market value for their homes, he decided to stay.

Johnson’s activism has gotten him arrested for breaking into buildings so the homeless would have a place to sleep. He was held at gunpoint for picketing a segregated doctor’s office. He’s taken the city of Dallas to court on multiple occasions to fight for homeowners’ rights and fair working conditions for the Dallas sanitation department. He even went on hunger strike for 18 days on the steps of old City Hall to protest poverty and hunger as part of Operation Breadbasket.

“We forced the nation to do something about hunger and malnutrition,” Johnson said. “For me, this was not a program for black people. It was a program for hungry people, for people missing meals, for people who couldn’t feed their children. … Out of all the stuff I’ve done, for me that’s the most precious.”

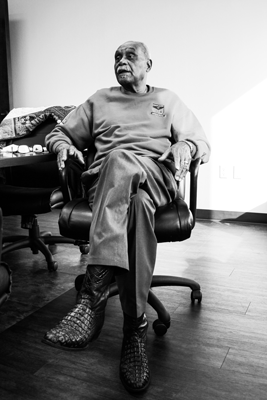

Johnson, now in his 70s, is still a big player in the activist community on both a local and national scale.

He is petitioning to rename the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, after Congressman John Lewis, a representative for Georgia’s 5th Congressional District and a civil rights activist who was beaten by state troopers on the bridge in 1963. Pettus was a Confederate Army officer and grand dragon of the Ku Klux Klan.

Johnson also has plans to march with King’s son Martin Luther King III in April near the Mexican border and deliver supplies like food and feminine products to refugees.

For three years, Johnson has been a lecturer and course planner at UNT and has insisted that a number of seats remain open for members of the community to attend his class, free of charge.

He hopes to ignite the passions of the younger generation as King did for him when he was a student.

“Don’t give up,” Johnson said. “Don’t accept the norm. You can change it. We did. Don’t give up and don’t despair. … The ball is in your generation’s court. … I have a tremendous amount of faith in America’s youth. … Speak out. Silence is a sin.”

https://eastfieldnews.com/2020/02/04/terror-in-iran-hits-home-for-eastfield-professor/