By LINDSEY CRAFT

@LindseycraftETC

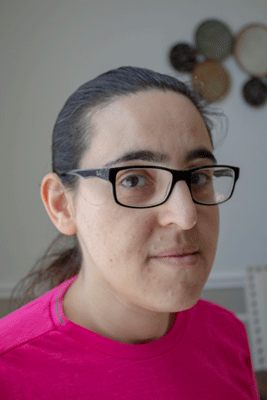

For months, Zeinab had been planning a trip to Iran to see her family. It’s been seven years since she left home and she was eager for her parents and brother to meet her 4-year-old son for the first time.

On Jan. 3, those plans were shattered.

Zeinab, a math faculty member at Eastfield, had just put her son to bed and sat down at the dining table to get some work done when she received a phone call from her husband urging her to check the news.

She went online and saw the report that President Donald Trump had ordered an attack that killed Iranian Gen. Qasem Soleimani the night before.

She laid awake at night for days checking the news wondering what was going to happen to her family in Iran, and herself, here in the United States.

“I’m not only worried about them surviving during a missile attack,” she said. “They’re also going to suffer from a shortage of food and medicine.”

Due to the rising tension between the U.S. and Iran, Zeinab canceled her trip. She feared she may not be let back in the U.S. just because she is Iranian.

She doesn’t know when she will be able to see her family again.

“My parents always wanted me to live with them or be around them, so it’s upsetting to know that I will never be able to go back to Iran,” she said. “I’m hoping I can get them here, but with the way things are going, my vision is that I won’t be able to see them for the next 20 years.”

For fear of her family’s safety, The Et Cetera agreed to publish only her first name.

According to the New York Times, a month since the attack, college students returning from Iran for the spring semester have been detained at U.S. airports. At least 13 students have been turned away despite having a valid visa.

‘Tied to sadness’

Zeinab is no stranger to war. She was born in the middle of the 1990-1991 Persian Gulf War between Iran and Iraq and grew up just two hours east of the frontline of battle in Kermanshah Province, Iran.

“My mom would always put me under the kitchen table so that if a bombing were to happen, we would survive,” she said.

Although she doesn’t recall experiencing any bombings of her own, close relatives were not so lucky. Some of her earliest memories are the constant grief her family went through following the war.

“Most of my childhood was tied to sadness,” Zeinab said. “Three of my uncles and 17 of my distant cousins were killed in the war.”

Her family members who died in the war weren’t in the military. They volunteered themselves to keep their families safe.

“Most of the people involved don’t approve of what’s going on,” she said. “They just have to protect the people they love.”

Once the war died down, Zeinab’s father decided to go back to school and study law. Her family moved from the small town she was raised in, to Tehran, the capital of Iran.

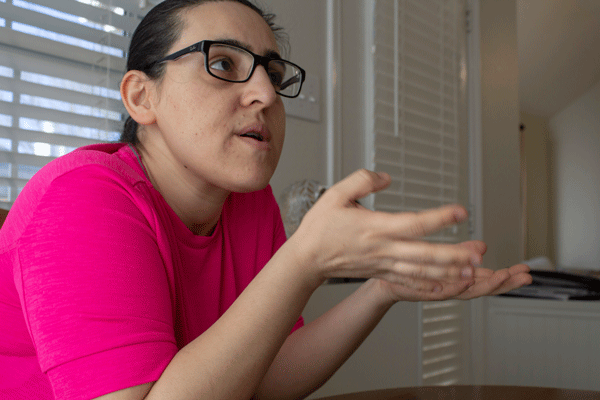

Zeinab attended the University of Tehran, where she often protested against the Iranian government. One protest started with just her and six friends and after an hour over a thousand people had joined in.

During that time there was a law that prevented officers from being able to enter the campus, so Zeinab thought she was safe.

Her confidence in safety vanished when officers raided the protest.

She was pushed to the ground and beaten, along with many others.

“They used tear gas and were hitting people in the head and body,” she said. “It was chaos, so we ran for our lives.”

This experience paused Zeinab’s activism. She was haunted by the ear-piercing screeches of her friends as officers beat them.

“I survived,” she said. “But I kept thinking that next time I might not.”

‘Diamond in the rough’

After graduating she planned to come to the U.S. to further her education and have access to better opportunities. She took the English-language exams and ended up getting a scholarship to the University of Regina in Saskatchewan, Canada. She accepted the scholarship in 2013, putting her one step closer to getting to America.

While in Canada, Zeinab met and married her husband. Together they applied to come to the United States in 2014. Her application was approved before her husband’s. She was accepted into the University of New Mexico and decided to leave without her husband while he waited for approval.

“Before coming to America, I was scared from what I’d seen in the news,” Zeinab said. “There are a lot of gun control issues, and there is a bad history between America and my home country. I was worried about being accepted as an immigrant.”

After a year apart, her husband was finally approved for a visa and met Zeinab in New Mexico. Zeinab earned her Master of Mathematics and Applied Statistics degree from the University of New Mexico in 2017. After graduating Zeinab did research on graduates from her school to see where they worked after college. She found that two previous graduates worked at Eastfield, so she decided to apply.

When she was hired, Zeinab worked as an adjunct faculty member until becoming full time in 2019. Jess Kelly, the executive dean of STEM, said having Zeinab at Eastfield plays an important role in welcoming students into an environment with a multicultural faculty.

“Having the breadth of diversity within our division is critically important not only to us, but to who we serve,” Kelly said. “We have a great faculty base, but she is special. Sometimes you just find a diamond in the rough … I feel very blessed to have her in our division.”

He said Zeinab lights up when interacting with students.

“You can see her drive and passion,” he said. “She comes here every day ready to engage with students, and that’s not something that can be taught. That’s a talent.”

Luz Ramirez, a former student of Zeinab, said her biased opinions of Iran were debunked after taking her class.

“The way Iran has been presented in my life was bundled with the Middle East and has led to false assumptions,” she said. “But professor Zeinab is just a teacher. She assigns homework, teaches her class and helps her students. She isn’t the person the media makes an Iranian out to be.”

[READ MORE: Dallas Women’s March celebrates voting rights]

‘He just needs to be a kid’

Zeinab considers herself a progressive Iranian American, although she’s not a U.S. citizen on paper. She converted from Islam to Christianity and doesn’t agree with the radical religious and political beliefs of Iran’s governing system, or the laws requiring women to wear a hijab.

Zeinab doesn’t wear a hijab, but she’s still had to deal with profiling and racism from people when she speaks Farsi.

“I remember I was talking on the phone with my family, waiting for the bus, and a man next to me told me I was speaking in an animal language,” Zeinab said. “I don’t get upset or mad. I believe people who lash out are having a hard time within their own mental state, and it has nothing to do with me.”

However, she does with that people’s views of Iran weren’t one sided.

“I feel so bad that the U.S. do not see Iran for the way it really is,” she said. “Yes, there is a group of extremists, but outsiders always overlook the people who are dying in the street while protesting against the government.”

Zeinab’s desires do not stray far from that of the average American.

She wants her son to be able to play, go to school and see his grandparents, like any other kid his age.

“As a kid I watched the news to see how the war was going, and politics were a common topic in my household,” she said. “My son is only 4 he doesn’t need to worry about the issues of the world. He just needs to be a kid.”

https://eastfieldnews.com/2016/12/07/assured-through-faith-muslim-professor-embraces-positivity/