By ARIA JONES

@AriaJonesETC

Laura Jarnagin was sound asleep. Then, a banging on her front door jolted her out of bed. She was terrified. As she peeked through her front window in the middle of the night, she saw four police officers outside, guns drawn.

“I’m going to open the front door! I do not have any weapons!” she hollered at them.

When they got inside, she was informed that her stalker had called the police and told them he was about to cut her head off. The police saw this as a viable threat.

They searched her entire house, including the attic, but didn’t find anything.

They asked her if she was OK. Physically, she was. But she lives in constant fear of violence. Her stalker had been to her home before.

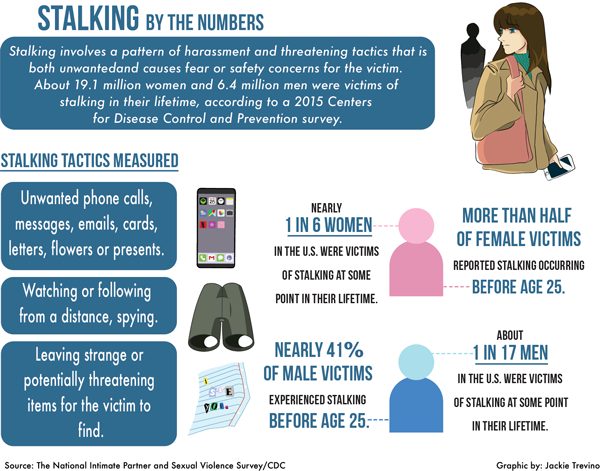

Jarnagin, who works in the president’s office at Eastfield, has been a victim of stalking for almost 30 years. She is one in six women who experience stalking, according to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey.

Stalking is a pattern of harassment that is unwanted and causes safety concerns for the victim. Examples of stalking tactics include making unwanted phone calls or sending unwelcome texts, emails, cards, or presents; watching or following; showing up at the victim’s home, workplace or school; leaving strange or threatening items for the victim to find; or sneaking into the victim’s home.

At Eastfield, there was one instance of stalking in 2017 and four in 2016, according to the annual security report. Counselor Jaime Torres said while stalking is more prevalent than other offenses, he is grateful there was only one report in 2017, with the Eastfield population having more than 15,000 students.

At North Lake College, student Janeera Gonzalez was shot and killed on campus in 2017. Her mother told WFAA that her killer had been stalking her.

Torres has been leading the efforts to provide training on these topics after the college received a grant from the Violence Against Women Act. The Bee Aware team has been created, a group of employees who work to prevent stalking, sexual assault and domestic and dating violence on campus.

A lawyer from the Texas Advocacy Project, which provides resources and free legal services, visited Eastfield Jan. 30 to provide information about stalking. Jarnagin decided to speak up when she attended.

“It can go from something as simple as a postcard in your mailbox to the police kicking down your front door because they think you’re being murdered,” she said to the attendees.

She wanted the young people in attendance to take the issue seriously and “not to just blow it off as some  kind of freak thing.” She felt like she could give stalking a face.

kind of freak thing.” She felt like she could give stalking a face.

Jarnagin started receiving notes in her mailbox in 1989 after her son went off to college. The sender went to high school with her son and had a romantic interest in him.

When she checked with her son, he remembered the person from school but didn’t have contact with him. Then Jarnagin began receiving strange phone calls in the middle of the night, with loud music playing, the stalker speaking incoherently or screaming into the phone.

She filed a police report each time, but the calls and postcards became more frequent and her situation continued to escalate. When they found him and arrested him, she found out that he suffered from mental illness.

Jarnagin said the district attorney was helpful. Her stalker was warned and there were hearings, but at the time her experience didn’t fit into the definition of stalking. She had no previous relationship with her stalker. She didn’t even know him. The office couldn’t decide what to charge him with and he was hard to locate.

In 2009, he was convicted of stalking and sentenced to 18 months in prison, but when he was released she said he started all over again.

A few days before the police banged on her door in 2014, the stalker had come to her home and thrown bricks through the front of her house. He had vandalized her home while she was away, throwing oil and defecating on her porch and drawing on her garage door.

She had a lifetime protective order issued against him that year.

The laws have changed since Jarnagin’s stalking situation began. Ashley Kolb, a lawyer from the Texas Advocacy Project said stalking, previously a misdemeanor, in 2001 became a third-degree felony, which could result in two to 10 years in prison.

In 2011, the term “following the other person” was removed from the Texas Statute.

“It used to be that defense attorneys were able to get a lot of cases dismissed because what the person was doing was not necessarily following,” Kolb said. “In this cyber age there’s a lot of ways to keep tabs on someone, trace someone, that doesn’t really fit a normal definition of following, and also there’s a lot of ways that you can threaten or scare someone without following them.”

In 2011, prosecutors were also allowed to introduce evidence of the facts and circumstances. Kolb said this was a game changer. Now juries could understand why behavior that may seem innocent out of context was frightening to victims.

“Imagine that a woman gets a bouquet of flowers from a man, and they say ‘I can’t wait to see you next week.’ That might not sound very scary,” she said. “That might not seem like stalking. But what if you had some special context? What if they came from a man who was incarcerated for sexually assaulting her and he gets out on parole next week? Well now you can see that is a threat.”

In 2013, stalking was linked to the harassment statute and the phrase “reasonably believes” was replaced with “reasonably should know.” She said before, the person being prosecuted could reasonably believe their behavior wasn’t scary when it was.

“There are people who stalk who have a skewed sense of reality and the facts,” she said. “They really believe that what they’re doing shouldn’t be scary, but a reasonable person would be terrified by it.”

Kolb said there have been some good changes in the laws, but a minority of these cases result in conviction.

“As you can see, [they are] really complicated, really convoluted and hard to prosecute,” Kolb said.

Jarnagin’s sister Cathy Odneal said the lack of legal protection is what let Jarnagin’s stalking get so out of control.

“I think it was just the legal system itself, the laws on the books, and to a certain degree, the stigma that came around it being a woman’s complaint,” she said. “It seemed to me, the whole entire time, that as many times as she had called, as many times as she had provided information, she still got no response.”

The police had their hands tied, she said. The lewd letters her stalker was sending weren’t violent enough for them to make it their top priority.

Odneal said it was the stalker’s call to the police, threatening to decapitate her sister, that sent things over the edge.

“I always knew that it was going to be something violent that happened before anybody would take it into account,” Odneal said. “You see examples of that every day and it still happens.”

Jarnagin was put in charge of her own safety and protection. She remembers a police officer strongly advising that she buy a gun and get training.

She keeps that gun near her when she’s home. She also has motion sensor lights and cameras around her home, a security system and all of her neighbors have been informed of her situation.

“I never go out of my house without looking and making sure that there’s no one hiding in the bushes,” Jarnagin said. “That there’s no one standing over beside the garage.”

Her sister said all she could do was encourage her to call the police every time something happened. She said it was often hard to find her sister’s stalker because he was on the streets. His options for mental healthcare are limited.

“There’s got to be a different way to address that as well,” Odneal said. “I’m not excusing what he did in any way, shape or form, but I think I understand a small portion of it.”

She said there is stigma around mental health, women and the police.

“All three of these things are working in conjunction to make things difficult to navigate and to accomplish what you need to accomplish out of them,“ Odneal said.

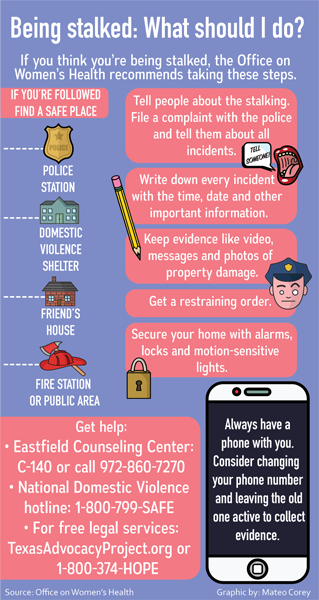

According to the Office of Women’s Health, someone who thinks they are being stalked should call 911 if they are in immediate danger and find a safe place if they are being followed. They should also file a complaint with the police, keep evidence, secure their home, tell people about the stalking and always have their phone to call for help.

Jarnagin hasn’t seen any evidence of her stalker being on her property in a long time, but it’s not a guarantee he hasn’t been there and avoided detection.

She said she has kept every piece of evidence of her stalking and urges others not to throw any letters, pictures or other evidence away.

“Be very, very careful and take it very, very seriously,” Jarnagin said. “Don’t just say ‘Oh, he’ll go away’ or let your friends tell you to just ignore him. Sometimes the more you ignore them or the more you don’t respond or the more you don’t do anything, the wilder they get.”

—Andrew Walter contributed to this report

https://eastfieldnews.com/2019/02/19/activist-survives-streets-assists-dallas-youth-homeless/