By Andrew Walter

@AndyWalterETC

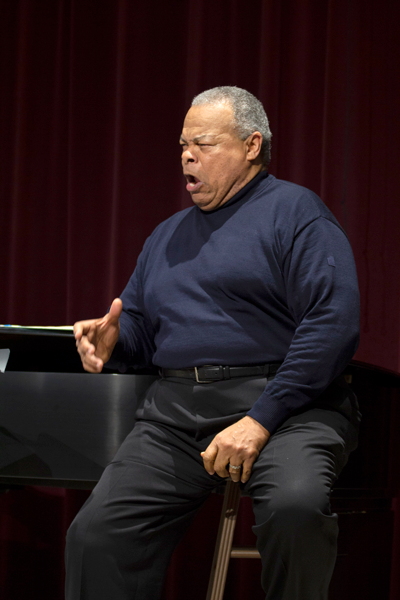

Donnie Ray Albert takes off his gray suit jacket, sits on a wooden stool and rests his right hand on a Steinway & Sons grand piano. His black shoes shine under the dim recital room lights at Eastfield College.

The Grammy award-winning baritone leans his head down for a moment, takes a slow, deep breath and prepares to sing “Mother to Son,” a song by African American composer Hall Johnson that is inspired by the works of poet Langston Hughes.

Albert explains that “Mother to Son” is about a black mother telling her son that the journey of life is more like a steep climb up a dark, broken-down high-rise stairway than a leisurely stroll down a “crystal stair.” He sprinkles in some humor to keep his audience just as engaged as they were when he was letting his booming, soul-shaking voice awe them on previous works such as “Genius Child.”

“I’m the mother,” says the large man in a tone befitting the presence of an opera singer.

The audience laughs, then falls quiet in anticipation. They’re a modest crowd comprised mostly of Eastfield student musicians. Their backpacks, guitar cases, recording equipment and boxes of sheet music litter the steps next to the rows of old, cushioned red seats where they sit.

Most of them are instrumentalists listening to an accomplished vocalist. Nearly all the vocal students are away at a competition. Even with this difference, the students don’t remove their gaze from Albert for the full hour while he performs works inspired by black poetry in the tiny recital room.

After his preface, Albert taps his fingers on an iPad sitting on the piano and nods at accompanist Julian Reed, who’s had more than 30 years of experience working in opera, indicating he’s ready to show these students that there’s so much more to African American music than just spirituals and jazz.

The senior lecturer in voice from the University of Texas at Austin’s Feb. 13 visit to Eastfield was part of the college’s Black History Month celebration and Wednesday recital series. Albert performed a handful of songs mostly composed by black songwriters and spoke about their relationship with black history.

Before Albert began singing, he jovially explained to the audience how there was a lack of diversity in his bachelor’s musical studies at Louisiana State University.

“I never, ever studied anything about one African American composer,” he said.

Following his studies at LSU, he attended Southern Methodist University for his master’s of vocal performance degree. Not until his last year there, when he was teaching at Richland College in 1974, did his studies involve African American compositions.

At that time, the new edition of Scott Joplin’s opera “Treemonisha” was produced by historian Vera Brodsky Lawrence in her most famous work, “The Collected Works of Scott Joplin.”

“Treemonisha” became important to Albert; it was the subject of the first paper he wrote on African American compositions, and it was the first opera he performed after graduate school.

He played Parson Alltalk for the Houston Grand Opera’s 1975 performance of “Treemonisha.”

“It’s funny how things work out in life,” he said. “That was the beginning of my saying, ‘Well, there’s more than two African American composers. [More] than just spirituals, than just jazz.”

Following “Treemonisha,” Albert starred as Porgy in George Gershwin’s Grammy award-winning 1976 production of “Porgy and Bess.” From there, Albert has performed in opera houses in New York City, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Mexico, Italy, Canada, Germany and more.

Albert used his sense of humor to tell the audience about the stereotypes of African American music. His audience was quick to laugh at his jokes. They would tilt their heads in captivation during tender moments in songs like “For You There is No Song” and leave their mouths agape when his voice thundered in songs like “Song to the Dark Virgin.”

“I enjoyed the way he set the atmosphere for each song, whether through anecdotal means or light humor,” said music student Calvin Neason.

Once the recital ended, Albert and Reed, who’ve worked together in performances such as “A Lifetime of Song” in 2018 at SMU, spoke with audience members about musical technique, their experience in the industry and what they said was most important for any musician: practice, practice, practice.

As someone who’s been a vocal coach, pianist, chorus master and conductor for operas across the U.S. and Europe, Reed could connect to many of the music students, since most of them were instrumentalists instead of vocalists. He suggested that they do both vocal and instrumental work.

“Your different muscle groups all do different moves [when you play an instrument],” Reed told one student. “Singing is the same way. You can work different aspects of it and have [your voice] drastically improve.”

Performing wasn’t always so easy for Albert. He told the audience about his childhood fears of singing.

He said that the piece “Mother to Son” was special to him because it was inspired by the Langston Hughes poem of the same name When he had to sing in at his family’s Baptist church, he froze and forgot everything about it when he took to the stage.

But right when the church’s organs would pipe up and the music started, he’d remember everything in an instant.

Growing up as a kid in the 1960s, Albert was shy and scared to sing in front of an audience. His fears made sense: It was the civil rights era, and Louisiana had its problems.

“That’s what true stage fright is all about,” he said.

During Albert’s Eastfield performance, Reed would follow attentively, raising his eyebrows as his fingers danced across the piano keys.

During one piece, both Albert and Reed suddenly stopped. Albert smiled at the audience, as if he were pretending to get stage fright at that moment, then he nodded at Reed and continued singing without losing the audience’s captivation.

While singing “Mother to Son,” Albert showed the audience that stage fright goes away with enough practice. He looked straight up into the glaring lights already pointed at him while singing, “Don’t you set down ‘cause you find it kinder hard.”

His voice swelled at that moment despite still being seated.

Then he rocketed off the stool and stomped his shiny black shoes against the aged, white tile.

“I’se still climbin’!” he roars, as if to symbolize the fears of stage fright he overcame more than 50 years ago.

Finishing the song, he sat down again, a triumphant grin on his face.

https://eastfieldnews.com/2019/01/30/borderlands-walks-in-the-line-between-arts-and-reality/