By SKYE SEIPP

@seippetc

A single bullet hit the front bumper of Kael Alford’s vehicle as she crossed the battle lines of Najaf, Iraq. She dropped to the floorboard.

She stayed there before being taken out of the car and forced to march with around 20 other journalists into the city overrun by Shi’a fighters and the stench of burning plastic.

“The journalists are here! The journalist are here!” they chanted in Arabic as she walked into the smoky desolate city.

On that day in 2004, American forces had planned to bomb the city, which would have destroyed the Immam Ali Mosque, considered the fourth-holiest site for Shi’a Muslims. Fellow photojournalist Thorne Anderson, now her husband, was also trapped in the city with a dead satellite phone.

“We wanted to tell the story from inside the shrine,” she said. “Within limits, because it was also an active battlefield.”

She talked her way into getting both the American forces and the Shi’a militia group to cease fire, allowing them to gain access for a press conference. But when the time came for her to cross the front lines, none of the other journalists were willing to go. A friend told her the only way to rally the other reporters was to get in the car and go.

“So I get in the first car and we go,” she said. “Everybody’s like, ‘Oh shit, she’s really going. We better get in there too.’”

Alford, a freelance photojournalist and adjunct photojournalism professor at Eastfield, has traveled the world to capture every angle of stories for more than 20 years now. From the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, to the effects of climate change on people in Louisiana, and her latest project titled “Dallas is Home,” which highlights different immigrants within North Texas, most of her work focuses on giving viewers a different angle than other media forms may be showing.

“I think it definitely helps to remind people of the common human experience when you’re trying to talk about the policies that affect people,” she said. “It’s when humanity gets removed from the policy that it gets easier to take a hardline and be exclusionary of others’ needs and vulnerabilities.”

“I think it definitely helps to remind people of the common human experience when you’re trying to talk about the policies that affect people,” she said. “It’s when humanity gets removed from the policy that it gets easier to take a hardline and be exclusionary of others’ needs and vulnerabilities.”

On top of her photography she has received prestigious awards like the Nieman Fellows Scholarship from Harvard University and the Knight Luce Fellowship award from the University of Southern California. Her projects from Iraq and Louisiana were also published into a book.

She originally went to college to be a writer and earned her undergraduate degree in English literature and archaeology from Boston University. She never took photography seriously until going to graduate school at the University of Missouri for in the mid 90s.

“I had a 35mm film camera that I had gotten for graduation from high school from my father,” she said. “But it was something I thought of as how most people [do] … I took it with me on holidays and made pictures of my ordinary life. I didn’t think of it as a tool for information gathering.”

Attending the annual photo of the year contest changed her view on the possibilities that photography had to offer. She said hearing the judges discussions made her realize that photography could be a way for her to tell the stories she had originally wanted to express in words in a more visual way.

“I was interested in traveling, exploring and going to learn more about the world,” she said. “I didn’t want to be stuck at a desk in a newsroom. So I found photography would be more likely to get me to that goal.”

She began living internationally in 1996 for her master’s thesis, photographing the culture of the Pomaks, a Serbic-Muslim ethnic group from the mountains of Bulgaria.

From 1992 to 1995, Bosnia — a country just to the west of Bulgaria and a former communist ally — was in a civil war that resulted in the ethnic cleansing of Bosnian Muslims and Croats by the Bosnian Serbs.

“The idea of civil war was something I wanted to understand better,” she said. “What would turn neighbors against each other? And since we come from a country that had a civil war, I think that compelled me.”

For the next seven years, she moved about Eastern Europe and parts of Eurasia, freelancing for various publications around the world. That was until March of 2003 when the bombing campaign began in Iraq. She packed up and headed to the desert.

Under the watch of the Iraqi Ba’ath party, she was driven around daily to see the aftermath of American airstrikes.

“We didn’t know if they would use us as human shields or take us to some location that was going to be bombed to get some Western casualties,” she said. “Every time we got on one of their buses,[we thought] ‘Where were they going to take us? What was really going to happen?’ It was really unnerving.”

Once the ground forces invaded, it became a free-for-all. The Ba’ath party disappeared, and any former members of the government slipped out of sight.

She spent the next year documenting the results of the war. At the time the American government said there were no civilian casualties, but her work showed otherwise. Pictures like the one she took of a young boy with his mother dying in a hospital bed were the “whole range of consequences,” as she called it, of the American policy.

“I just wanted to be sure people in the United States understood the human costs of the war and didn’t just hear the ideological agenda from the U.S. government of this fantasy narrative about what was going to happen and what it would be like,” she said. “I wanted people to see. I wanted to ground truth of that policy and say, ‘OK this is that policy. This is what the consequences are of that policy’”

As a journalist, she said it felt like her job was to read between the lines and show the ramifications of the war on everyday people. She hoped her work would shatter the realities that some Americans believed about the war.

After almost two years in the Iraqi desert showcasing the death, calamity and anarchy of the war, she decided to move back to the states. But stepping on American soil didn’t alleviate her stress. Instead it made her feel like a “failure.”

“Doing that kind of work has a way of making you feel like that’s the most important thing in the world and nothing else matters,” she said. “Because … this tragedy is playing out before your eyes, and I tended to feel like if I could only record it well enough … then surely people would see the fallacy of this course of action and at some point reconsider.”

Her feelings of inadequacy at leaving felt like that of a soldier wanting to be there for their squadron. But unlike a soldier wanting to protect their fellow troops from harm, she said her duty was to “wake up” the decency of humanity.

“I never felt like there are Iraqis or there are Americans and I’m one or the other,” she said. “I just felt like a person in a set of circumstances that was bad for everybody. … It didn’t really matter that I was American … but I happened to have personal skin in the game because this was being done in the name of me and my government. So that made me extra motivated.”

She moved to New York City in 2004, but working as a freelancer overseas for her entire career meant she didn’t have any real connections with editors, and journalism doesn’t typically pay enough to afford housing in NYC.

In search of a cheap place to live, she saw an ad for an apartment that offered low-rent in exchange for dog sitting while the tenant was out of town. Since she just left her dog in Amsterdam, she decided to call. Dionne Searcy, who is currently the West African Bureau Chief for the New York Times, answered the call. She was coincidentally packing for a trip to Iraq for the publication Newsday.

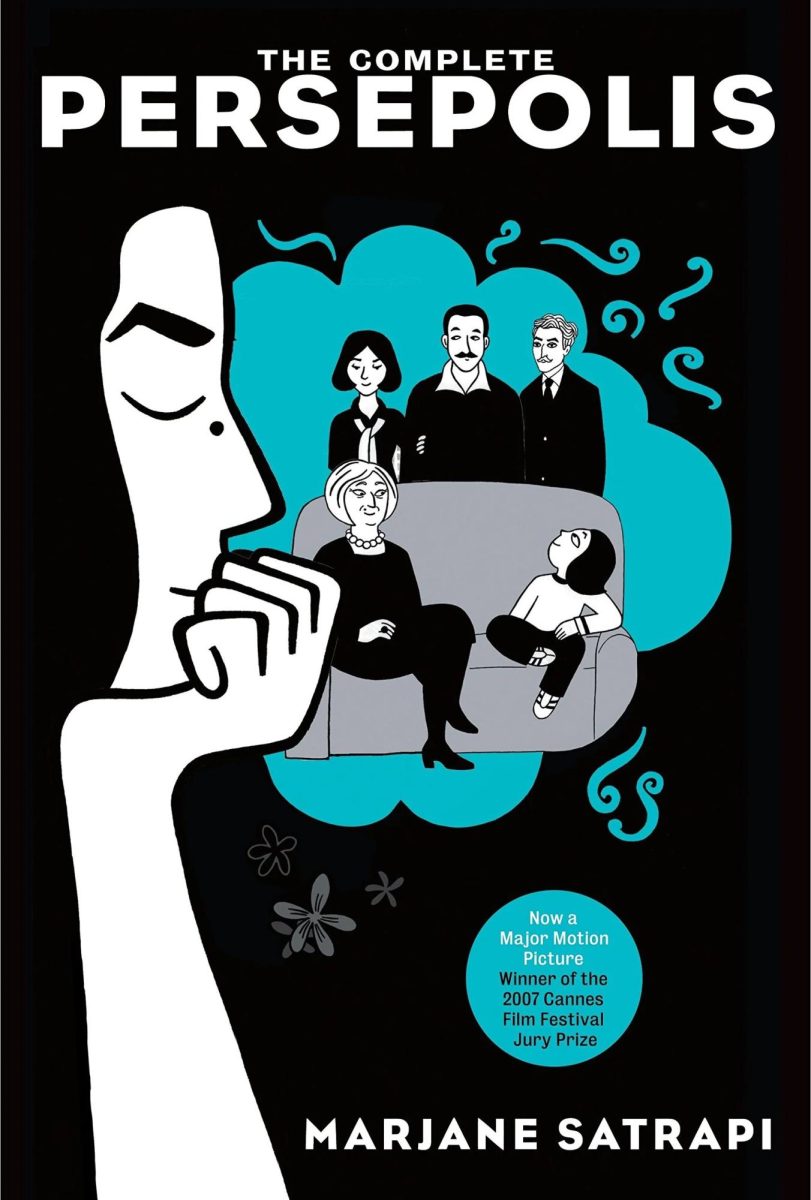

With a place to live now, Alford began wondering how she could show her work from Iraq to more people. She had the idea to bring in three other photojournalists, one being Anderson, her husband, to set up an exhibition and print a book titled “Unembedded.”

The book focused on the Iraq invasion from the lens of four freelancers. It allowed them to not only bring their work to a larger audience, but to explain what they saw while they were in the Middle East. The exhibition was installed in galleries and museums across the country, with the last installment being in 2013.

“I was so frustrated because I was one journalist, and as one journalist, alone, you don’t make much of a dent in the overall narrative,” she said. “You don’t get a chance to really tell the story as you see it if you’re just taking assignments all the time. You’re just supplying photographs for somebody else’s story.”

Alford said most of the people who came out to the presentations were already opposed to the invasion, but others called her a “traitor.” She noted one mother who brought her child to the exhibit. Worried that her photos of war and death would scar the child, what she heard instead was the child recognizing the realities faced by other children around the world.

In between her showcases, she began working on a new project in 2005 titled “Bottom of da Boot,” which showed the crumbling environment of Isle de Jean Charles and Pointe-aux-Chenes in Louisiana, whose communities trace their lineage to French settlers and Native Americans who escaped the Trail of Tears.

“It’s a climate change, fossil fuel, indigenous, colonial, post-colonial story,” she said. “It’s very much a case study of our time.”

With genealogy on her grandmother’s side traced to the area, she felt it was her mission to photograph the effects of disasters like Hurricane Katrina and climate change had on the region.

In April of 2010, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico ruined the water in the area, spreading into places the locals had deemed sacred territory. Some of them being grave sites. And Alford was there to document the intoxicating wasteland that was created by the disaster.

“What they were left with is this ecologically degraded landscape that’s succumbing to climate change,” she said.

During the middle of her work in Louisiana, she was awarded a Nieman Scholarship at Harvard University from 2008-2009, which brings together journalists from all over the world to work and learn together at the prestigious institute. She also moved to Dallas around this time after her husband accepted a job at the University of North Texas.

As her “case study” was coming to a close, she returned to Iraq for a month to check in on the people she had left in 2004 and to see the landscape seven years later.

“Iraq was just a very different place,” she said. “There had been a civil war. Neighborhoods were segregated and divided between different religious or ethnic groups. There were tons of internally displaced peoples across the country. … Overall the country had just been at war since I left. They never had a break.”

One widow of a Shi’a family that Alford knew from Baghdad was raising seven children alone. Her husband died in the Iran-Iraq war, and Alford said two of her sons were involved with resistance movements, whether they wanted to be or not.

At the time of her 2011 trip, one of the sons was hiding from militias looking to recruit him. The other disappeared while Alford was visiting, and she helped the mother search for him. They later found out he was imprisoned.

The rest of the children were still school-aged, but with a hodgepodge government running the country, there wasn’t much support for the widow.

“The schools weren’t working well, and she didn’t have any pension from the government anymore,” Alford said. “They were just piecing together an existence.”

Back in Dallas, Alford began working at Southern Methodist University teaching art photography. In 2014 she had her daughter, Rosalie.

About three years ago she started teaching at Eastfield as an adjunct professor.

In that time she has had to adjust her life a little, but she continues to work on projects, such as one that she did for a magazine in Sweetwater, Texas on climate change.

In January she started her latest project, “Dallas is Home,” which debuted in the lobby of City Hall the week of Sept. 9. The project highlighted immigrants from around the world who live in North Texas. She said it began out of her desire to show a human aspect of the current hot-button political issue of immigration.

“I’m just hoping to create a space in our city where people hear from immigrants and migrants directly,” she said. “Rather than through the lens of a media narrative about what immigration concerns us. Like right now the conversation is immigration or migration as a problem. … When the human story is a story of migration.”

With the help of Dianne Solis, a reporter for the Dallas Morning News, the two began interviewing different immigrants from the community to show their life in the states upon moving to America.

In the exhibition, the viewer is shown a series of photographs of the subject, while a recording of their interview plays during the slideshow.

In between the project and being an adjunct professor, she also gave birth to her 5-month-old son, Aven.

His cries echoed through the monolithic lobby of Dallas City Hall as Alford was curating the reception for the project. She stepped away from the project and began nursing the baby. At that moment there was a malfunction in the show. With Aven still suckling, she fixed the issue and went right back to leading the exhibition.

One of the subjects was Stanley Ukeni, who immigrated to Dallas from Nigeria after seeking asylum from the tyrannical government of his home country. After settling down with his wife and two kids in Dallas, he was deported from the city he had called home since the 1990s and was kept for years in Africa awaiting trial.

He eventually won his case and was able to return to Dallas. When Alford asked him to be a part of the project, he looked her up on the internet and saw she was more than qualified to tell the story. .

“It also advances a narrative that immigrants are human beings,” he said. “They have their own stories. Their own hopes, aspirations, pains and triumphs. Just like every other American citizen. … I think it’s admirable that she’s doing this.”

Working with her on the project was former Eastfield digital media student and aspiring photographer Kate Arrows, who met Alford in fall 2018.

When the time came for Arrows to get an internship this past summer, Alford was the first person she called. Arrows figured she would know of someone that had an open internship, not expecting it to be herself.

She said working with Alford allowed her to see the calm, linear approach that she brings to a project like “Dallas is Home.”

“She’s an excellent instructor, and her passion for helping others is unlike anyone I’ve ever met before,” Arrows said. “She’s inspired me to think about how I can make my talents help other people and give them a voice.”

Alford may not have to face a blistering desert sun and bullets flying at her car on a regular basis anymore, but she’s still dedicated to showing the world through a new lens.

When asked how she balances being a mother, teacher and freelancer, she simply said: “You’re looking at it.”

As she sat on the floor playing with Aven and Rosalie’s flashcards laid sprawled out on the coffee table, covering up the latest issue of the New Yorker.

“It’s pretty inextricable of who I am as a person,” she said. “I can’t not keep my mouth shut or my hands out of it. I hope these kids grow up to see that if there’s something they think is not right in the world with the way things are happening and you have the power to say something or do something about it, then you better get involved in some way. That’s the only way things can change. Powerful wealthy people will rule this planet unless enough people who are not as powerful or wealthy get involved to shift the direction otherwise.”

https://eastfieldnews.com/2018/02/14/photography-that-makes-an-impact-ortega-travels-the-world-to-tell-true-stories-visually/