By JAMES HARTLEY

@ByJamesHartley

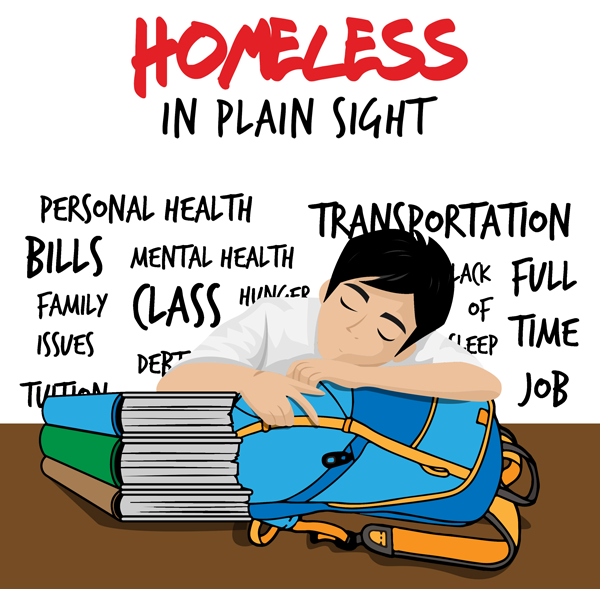

Homelessness and housing insecurity have joined food insecurity, debt and inability to pay for textbooks and tuition on the list of financial struggles plaguing the campuses of American colleges and universities.

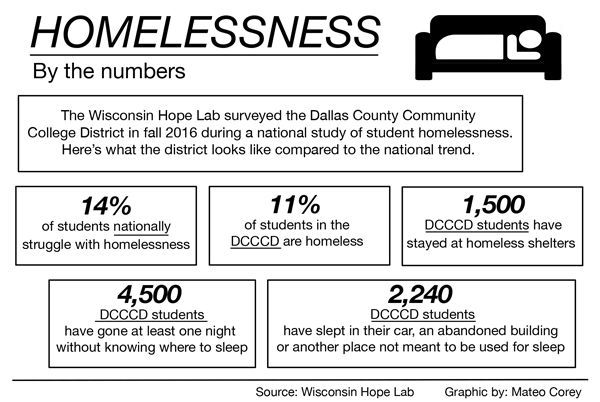

Nationally, 14 percent of students struggle with some form of homelessness, according to a fall 2016 study conducted by the Wisconsin Hope Lab.

While the Dallas County Community College District does not present the same tuition burden as four-year institutions across the U.S., it is still affected by this national trend of students struggling to find a place to sleep.

Eastfield counselor Katie Neff said it’s hard for students to focus on their academics when they’re having to worry about food and housing.

“It impacts, psychologically, students who don’t have the basic foundation of food, shelter, being able to have clothes,” Neff said. “If somebody’s living in their car, couch surfing, there isn’t that stability for them. That can make it difficult or challenging for them to focus on their studies or complete their homework.”

According to the Hope Lab survey of the district, 11 percent of students in the DCCCD were found to be homeless.

Among those who indicated homelessness, 6 percent surveyed — almost 4,500 students — went at least one night without knowing where they would sleep.

Nearly 1,500 students said they stayed in a shelter and about 2,240 said they stayed in an abandoned building, a vehicle or another place not intended to be a house.

[READ MORE: Campus food pantry to open after initial delay]

Finding resources

While the DCCCD has plans to create student residential facilities that may help alleviate housing insecurity, there is currently little in Dallas County directed specifically at assisting college students find a place to sleep or call home. There are shelters, but none specifically for homeless college students.

Neff said that in the meantime, it’s important for the DCCCD to connect students in need of housing with resources that are available.

She keeps a list of local shelters on hand, complete with phone numbers, addresses and websites and encourages students to contact the DCCCD Navigators, a team of staff dedicated to helping students with anything from registering for orientation to getting food, clothing and shelter.

Brochures and flyers directing students to aid are especially useful because many of these students don’t have internet access outside of campus, Neff said.

Lisa Cook, a navigator working specifically with Eastfield, said most on their team have been students at DCCCD schools, so they have a special understanding and empathy for the things students are going through.

“We are there for anything the students need,” Cook said.

When it comes to housing insecurity, food insecurity or other troubles outside of college, navigators help students work through My Community Services, a program designed by the company Aunt Bertha to connect DCCCD students to resources.

Students can access My Community Services themselves, but Cook said navigators can help determine which resources best fit their needs.

Craig Satterfield, executive dean of student enrollment and services at the DCCCD LeCroy Center, said the navigators are also interested in making sure students going through hard times have support with their academics.

“If a student is, for example, facing homelessness or is currently homeless, we experience that sometimes there are other issues that carry over into their academics, and we need to talk to them about how their classes are going,” Satterfield said. “It carries over into their work life. We’ll have a discussion about how is the student as a whole needing any other assistance.”

Deeper roots

Homelessness does not always start in college. After8ToEducate, a social services group partnered with the Dallas Independent School District, estimates 4,000 Dallas ISD students are homeless, 500 of them in high school.

“That’s a conservative estimate,” After8ToEducate executive director Hillary Evans said. “That includes couch surfers, individuals that might be living in motels. It’s really blurred. I think a lot of youth don’t even know they’re homeless under the federal definition. There’s also a stigma attached to being homeless and maybe wanting to fly under the radar.”

Starting late spring or early summer, the organization’s Fannie C. Harris Youth Center will begin offering beds to homeless students enrolled in the Dallas ISD, focusing on high school students.

For now, the center offers a drop-in center where youth aged 14-21 can shower, do their laundry, eat hot meals and get clothes for school.

It will soon offer social services to help students find stable housing and connect high schoolers with colleges or technical programs.

While there are no formal partnerships with colleges and universities in the area specifically to help high school students transition to higher education, that is something Evans hopes to see in the future.

The resources for college students in the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex are fewer and not as focused or developed.

[READ MORE: Homeless students need attention now]

New studies

Urban Theory, a task force founded by Tarrant County College project manager Jesse Herrera, is one group studying student homelessness and trying to find solutions.

“We already know some broad things that are contributing to this particular problem,” Herrera said. “We’ve got a decent understanding of some of the challenges they’re dealing with and how to frame some potential solutions for the problem.”

While Urban Theory is still a young group — he licensed the group four years ago but started work in earnest last year — Herrera thinks they have a chance to impact students not only at Tarrant County College but across the metroplex.

The group’s work on student homelessness is still in the research phase, but Herrera said they should have enough information to begin planning by the second quarter of this year.

So far they’ve found that most students impacted by housing insecurity are 18 to 25 and don’t come from any specific type of demographic.

Students consistently report coming from hostile environments in interviews conducted by Urban Theory.

Many students became homeless trying to flee a violent home environment, in many cases some form of domestic abuse.

“The home that they go home to isn’t very safe and isn’t conducive to education,” Herrera said. “It could be a significant other who is verbally abusive or physically abuse or both. It could be the same with a sibling or a parent. In one case we actually had a mother who had verbally abusive children, so it made her home somewhat hostile.”

Many students will sleep in their cars, couch surf and spend as much time on campus as they can. Some end up on the streets and a few are utilizing shelters, Herrera said.

Shelters, though, can also prove to be hostile environments to students. Some students have told Urban Theory that policies, such as no texting or computer use in the shelter, make it difficult to study.

Herrera expects that many of the findings in Fort Worth will be the same in the rest of the metroplex.

While Urban Theory has been working alone to analyze data gathered thus far, Herrera would like to partner with researchers and nonprofits for more scientific results to his study.

He’s also looking for organizations willing to share data and work together.

Existing initiatives

Other organizations across the U.S. have had success in helping to relieve homeless insecurities on campuses.

One organization, Students 4 Students, was founded to help homeless students when doctoral candidate Louis Tse at the University of California Los Angeles noticed a large homeless population on campus and wanted to come up with a solution.

The organization is run by 200 volunteers attending UCLA with help from 100 community leaders, college administrators and faith leaders. Its $65,000 annual budget comes mostly from donations and grants, with philanthropists pitching in big, according to Lori Klein, executive director of Students 4 Students.

Students 4 Students’ Bruin Shelter offers 10 beds to students without places to sleep as well as food and assistance in connecting with resources. The organization is run almost entirely by volunteers, most of them students or alumni of UCLA.

To date, the organization has sheltered 36 students, 90 percent of whom have either graduated or are still enrolled according to Klein.

She said the organization could serve more students if they didn’t allow people to stay as long as they need, up to an academic year. But the current policy allows them to make a deeper impact on students, she said, giving them a safe place to study and sleep without worrying about their next meals. That impact is what the Bruin Shelter is all about. It’s connected an additional 200 students with resources to help with affordable housing, food and other needs.

“College students have enough to worry about just graduating,” Klein said. “When there are students that are homeless and trying to figure out where their next meal is coming from, where they’re going to sleep, when they’re not getting that sleep, it’s really hard to focus and maintain that GPA.”

Getting students to graduate is the main focus of Students 4 Students. To help with that, the services go beyond just housing.

Social work and medical majors volunteer to put residents of Students 4 Students in touch with resources, while other volunteers help with food and other essential needs. The organization is eager to share their success.

Klein said the focus will stay in Southern California for now — Students 4 Students is working to open a Trojan Shelter with the same design as the Bruin Shelter in the near future — but would like to eventually help others from outside the region start similar projects.

https://eastfieldnews.com/2019/02/19/activist-survives-streets-assists-dallas-youth-homeless/